Humanity at stake ? Humanitarian challenges and response in a complex and insecure world

Speech given by Mr Peter Maurer President of the International Committee of the Red Cross Tsinghua University

Dear colleagues

It's a pleasure to be addressing you today and a delight to be visiting your country. China is an important partner for the ICRC and it is my fourth visit here. This week I am meeting with key authorities, with business, the academic community, to discuss issues of common interest, both here in China and in the places that we both work.

In its effort to respond to humanitarian challenges across the world, the ICRC needs strong support from all countries, including China. In Geneva and in the countries that I visit, I make a point of meeting with representatives from the Chinese Government because of the increased role that China plays today in the international system. In fact, two weeks ago I was visiting our operations in the Democratic Republic of Congo and had an in-depth discussion with the Chinese Ambassador there.

As we have seen in the video, the International Committee of the Red Cross is the lifeline for people in places of armed conflict and violence. The ICRC is also the guardian of the Geneva Conventions, the laws which govern how wars can be fought and which limit the suffering of civilians and others. The ICRC is neutral and independent, meaning it does not take sides in a conflict and is focused on ensuring we can provide humanitarian relief and protection without discrimination. It respects the national sovereignty of States and, at the same time, it engages with all the parties to conflicts about their obligations. As an organization we are focusing on armed conflict and other situations of violence; at the same time we are at the origin and part of the RCRC Movement with its 190 National Societies and which in each country has a mandate to respond to a large bandwidth of social and environmental crisis and wherever we can, we support the Federation and National Societies in their endeavour as much as they are our first partners.

President Xi Jinping has recognized the importance the principles of the Red Cross and when addressing the United Nations in Geneva last year, reinforced that: "In the face of frequent humanitarian crises, we should champion the spirit of humanity, compassion and dedication and give love and hope to the innocent people caught in dire situations. We should uphold the basic principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence".

The ICRC has been working in more than 80 countries across the world, sometimes for decades, and has a deep knowledge of the complex factors that are driving instability, conflict and violence.

The ICRC has seen first-hand the impact of wars on civilians and know only too well that the humanitarian challenges of our world today are vast. For example:

- 2 billion people are affected by fragility, conflict or violence;

- 65 million people are displaced - the highest number since the Second World War;

- It's estimated that 26,000 civilians were killed or injured in attacks last year in just four countries : Afghanistan, Iraq; Somalia, Yemen;

- The numbers of people reported missing in conflicts is huge: in Iraq, for instance, estimates are there are between 250,000 to 1 million missing persons from past and current conflicts;

- The number and severity of attacks on health care – against patients, health workers and hospitals are grave: and the ICRC has recorded almost two incidents per day on average, just in 16 countries;

- We see disturbing mortality rates for particularly vulnerable groups: for children under five, newborn survival rates

- The annual economic impact of conflict and violence is $14 trillion - or 14% of global GDP.

Around the globe, we have been witnessing a rapid transformation of conflict dynamics over the last few years. I would like to share five key trends that may shape the future of conflict, and therefore the humanitarian response.

One, conflicts are increasingly protracted – and they are more often fought in urban areas.

In the ICRC's ten largest operations, we have been on the ground for an average of 36 years... in some places for 60 years. The result of decades of fighting and on-going violations of the laws of war, have destroyed basic social infrastructure, health, water and sanitations systems and have stalled education and economic development. Actors on the ground are increasingly fragmented, alliances are changing quickly, and weapons are easily available and are being misused.

- In Yemen for example less than half of the health system is operating. 16 million Yemenis require assistance to access to healthcare, including a staggering 9.3 million in acute need. Last year in an entirely preventable epidemic, we saw a cholera outbreak threaten the lives of more than one million people. With the rainy season approaching in Yemen we expect the broken health system to be again overwhelmed with a crisis.

The consequences for humanitarian work are far-reaching:

- We need to respond fast and slow, in emergency and on systemic challenges;

- In urban settings, we have to engage with many actors to generate consensus for humanitarian work; and

- The politicization of issues, as well as the dimensions of problems, are challenging neutral and impartial humanitarian action.

- Needs are transforming rapidly in today's conflict: basic needs, psychosocial needs, connectivity as needs. Needs are individual and systemic in character. They are short term and long term and they are different depending on contexts.

Two, there is a shocking lack of respect for the basic principles of international humanitarian law when it comes to the conduct of hostilities, the way war is being waged and the way weapons are being used.

Additionally we see the inhumane treatment of detainees, a lack of protection of civilians and the disregard for the specific needs of women, children, the elderly.

Fundamentally, whatever the conflict, whoever is involved, IHL is the standard that we must apply so that wars have limits and human suffering is reduced. IHL is the tool that helps warring parties find their way out of difficult, entrenched situations and prevents conflicts from spiralling, ensures minimal consensus amongst belligerents.

Instead, though we are seeing military strategies unfolding where civilians become the primary object of attack rather than being the primary object of protection. There are concerning attitudes to denying the fundamental rules of war and we see:

- Transactionalism, where the law is traded with arguments like: "I'll give you information on missing people if I get my prisoners released";

- "Exceptional circumstances" cited as reasons for applying IHL selectively;

- War on terror and fighting extremism used as an excuse to indiscriminate use of force;

- Other trends make the application of the Law difficult: partnered warfare, alliances, indirect warfare, and secret warfare. Our challenge is to clarify with belligerents the roles and responsibilities towards State and non-state partners to ensure respect for the Law.

Three, fragility – where there is a growing concentration of risks such as income inequality, poverty, youth unemployment, violence and criminality.

In many places violence is increasing, fuelled by the drug trade, unemployment and civil unrest. Sporadic violence becomes a feature of everyday life and can even spiral into full-blown conflict.

Different types of violence – politically motivated, criminal, inter-community – are unfolding on top of each other, meshing together into an inseparable mess.

- For example: In Rakhine State, inter-community conflict between Muslim and Buddhist communities has spilled over into intense violence causing hundreds of thousands to flee. Far from being only a local problem, the issue is infiltrating and dividing the international agenda. Each and every step in humanitarian assistance and protection for the Muslim population in Rakhine today leads to political polarization in the international community.

- Example Latin America

Four and globally, a lack of political solutions to end conflicts or to mitigate their effects.

The regional and global dimensions of conflicts are of serious concern, as the dynamics are less and less conducive towards political solutions. Instead they can they can trigger new layers of conflict on top of the existing protracted ones.

These power dynamics at global, regional, national and local levels are increasingly interlinked and do not only make political solutions elusive, they further complicate preserving a neutral humanitarian space. We see humanitarian action is contested, politicized, and often used as a bargaining chip in the struggle for power.

And finally the fourth industrial revolution is bringing challenges and solutions that we are only beginning to understand.

Just to highlight one aspect on the methods of warfare: innovations that yesterday were science fiction could cause catastrophe tomorrow, and include combat robots, cyber-attacks and laser weapons.

It is said that the world is already in a new arms race involving the rise of lethal autonomous weapons. The ICRC is concerned about the serious risks posed by increasingly autonomous weapon systems, which are enabled by advances in robotics and artificial intelligence, including data-driven machine learning algorithms.

While there is broad consensus that humans should retain a role in the operation of autonomous weapons, there is a profound and urgent need for the international community – including States, the tech industry and arms developers – to agree on the type and degree of controls that are needed.

Dear colleagues, the magnitude and difficulty of the humanitarian challenges today, and into the future are nothing short of humbling. I would like to offer some of the ways the ICRC is responding:

Continuing to urge greater adherence to international humanitarian law, especially the importance of refocusing on protection and changing behaviour.

The critical question for the ICRC is how to change the behaviours and policies of belligerents, and our research with several armed forces and non-state armed groups is providing fresh insights. We are discovering that a frontline fighter is more concerned about the views of peers than the punishment of commanders: meaning prevention of violations is often driven horizontally between combatants or through pressure of local communities on the fighters, rather than vertically by authority.

If we can better understand the patterns of restraint – as well as the patterns of violations – we hope to be better able to generate greater respect for IHL.

Rethinking our engagement with affected people

I firmly believe that we will only be able deliver more impactful humanitarian responses by ensuring people and their needs are at the centre of all that we do.

But to really understand what people need is not straightforward. People's needs are complicated. The dynamics of contexts, where the ICRC operates are not linear. We work both in areas close to the frontline, where people are forced to flee their homes; yet just kilometres away there may be areas where people are trying to rebuild their lives. The first group needs shelter, food, blankets, the other needs the taps to be turned on, for electricity and medical services to operate.

We need to understand the realities of what is happening on the ground and to be flexible enough to shift when the demands change, or when the assumptions about what is needed, does not reflect the real needs.

We are forming new forms of multi-sector partnerships, to pool expertise and resources and make humanitarian work more effective, impactful and innovative.

In our partnerships with the private sector, we started moving away from a simple donor/recipient relationship some time ago. Today, we have an increasing number of partnerships that bring together the skills and interests of humanitarian organizations and businesses to solve difficult problems.

- Example: Novo Nordisk and non-communicable diseases – creation of a sustainable supply of insulin for diabetes patients.

We are also partnering to test innovative funding streams, including instruments with market elements or market based.

- Last year, I was pleased to launch the world's first humanitarian impact bond to create a new capital stream to fund our work in physical rehabilitation centres. This is based on a pay-for-results model and involves private funders as well as government. In some ways this is a radical step for the ICRC, but also a logical one as we test opportunities not only to modernise the existing model for humanitarian action, but also new economic models, designed to better support people in need.

Digital connectivity too is allowing us to design more impactful solutions, based on people's self-identified needs, and for more efficient coordination between services. With business and scientific communities, we're working to use the potential of big data to analyse contexts and needs and to test new platforms for cooperation.

The field of innovation is by no means limited to technological and financial developments. Over the last few years we have, as part of an exchange with leading universities, created the Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation, a promising global network of practitioners to develop specialist expertise in frontline negotiation.

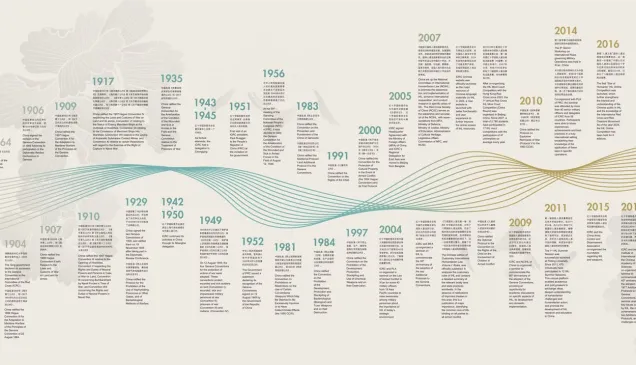

Dear friends, in all the challenges and solutions I briefly touched this evening, I'm deeply convinced that China, as a rapidly developing and responsible global power, has a lot to bring to the humanitarian global effort and, in particular to the ICRC mission. A year ago this month I last visited Beijing and was one of the international guests who spoke at the Belt and Road Forum. The links between the Belt and Road initiative and the ICRC may not be all that obvious at first, but we have been taking a keen interest in its development. The ICRC has been working in many of the countries along the Belt and Road, sometimes for decades, and has a deep knowledge of the complex factors that are driving instability, conflict and violence. That's why I'm deeply convinced that the Bet and Road Initiative, should take into consideration the humanitarian challenges at stake where conflicts and other situations of violence are prevailing alongside the Belt and Road. We need only a green Belt and Road, we also need a Humanitarian Belt and Road.

As I have the privilege tonight to meet with students, you who will be the leaders of tomorrow, let me emphasize a topic which is important to me: the human dimension of the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement. We are a people-centered organization, responding to the needs of the victims of conflict and violence, but also made of people from all over the world. Today, with our headquarters in Geneva, ICRC operations stretch to conflicts around the world, staffed by some 16,000 people from 130 different nationalities. Just few of our staff are Chinese, and I would be very pleased to recommend the ICRC to you as a rewarding place to bring your expertise and grow your career. Our staff members come from almost every professional background – while we have doctors and nurses, we also have engineers, detention advisers, forensic scientists, logisticians, psychologists, weapon contamination experts, data specialists among others. First and foremost, we need diverse people able to understand and work in difficult contexts.

Dear friends, the challenge of preventing, responding to and recovering from the suffering we see in the world is immense. And the solutions are complex and multifaceted. But we have many of the tools and approaches at our disposal – international humanitarian law, neutral, impartial humanitarian action, collaborative partnerships... all bolstered with the concern and actions of interested people like yourselves who are contributing their ideas, energy and leadership.

Thank you.