Humanitarian action and the pursuit of peace: Speech on the anniversary of the Nobel Peace Prize

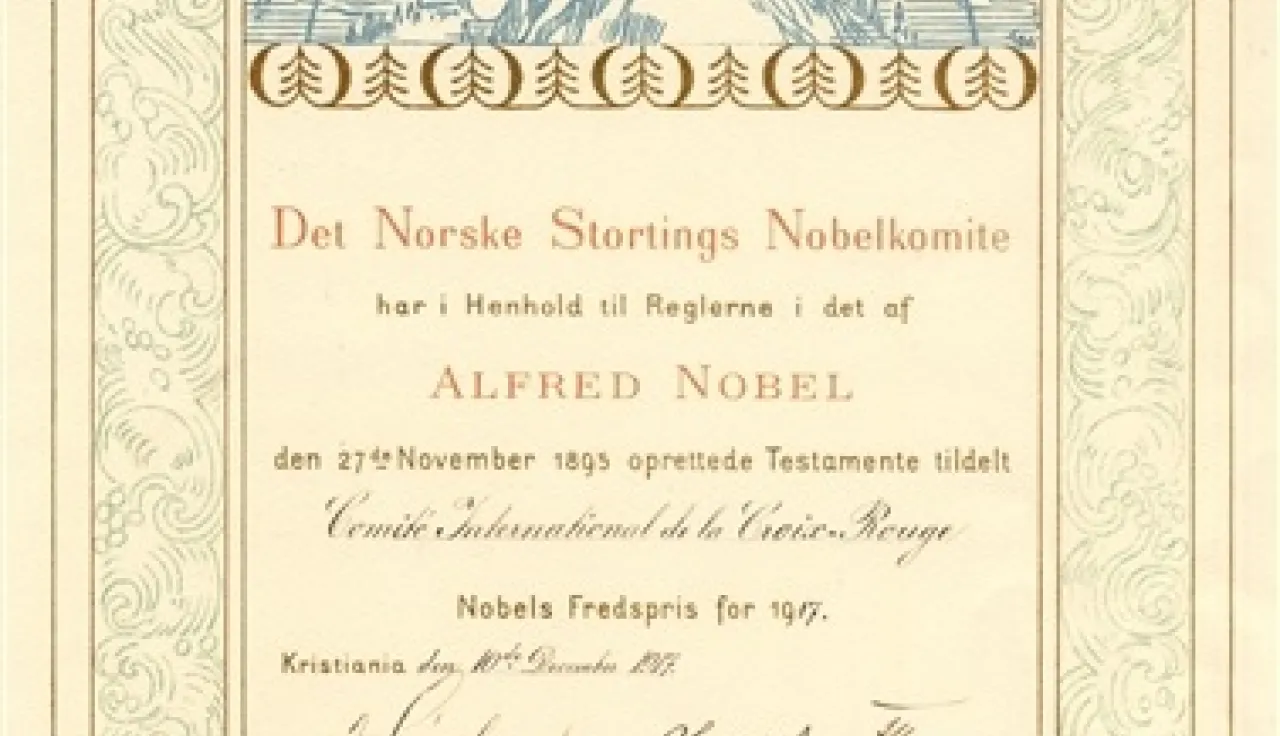

Red Cross and the Nobel Peace Prize

No recipient has been awarded the Peace Prize as many times as the ICRC.

In 1901, the first ever Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Henry Dunant, founder of the Red Cross, whose whole life was guided by a passionate devotion to the humanitarian cause. The ICRC was then awarded the Nobel Prize in 1917 and 1944, as a tribute to its humanitarian activities during the two World Wars, and again in 1963, together with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

Speech given by ICRC President Peter Maurer for the Fondation Gustave Ador, 8 June 2017, Geneva.

"It has been claimed that rather than looking for ways to make war less deadly, we would be better off tackling the problem at its source and working on universal, permanent pacification of the world. Listening to our detractors, we gather the impression that all we are doing is legitimizing warfare as a necessary evil. Is this criticism really justified? I am sure it is not. Of course, as much as and even more than anyone, we want people to stop killing each other and we repudiate this vestige of barbarity which they have inherited. (...) Moreover, I am convinced that by organizing assistance for the wounded, by making heartfelt appeals on their behalf to the general public, by arousing pity in telling of their misery and exposing the appalling spectacle of the battlefield for our cause, by uncovering the terrible reality of war, and by speaking out, in the name of charity, on that which politics too often would prefer to keep hidden, we will do more for disarmament than those who use economic arguments or vapid, sentimental orations."

Those words were spoken in 1863, at the opening session of the conference which led to the creation of the Red Cross. Gustave Moynier, one of the founding fathers of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, was anticipating the criticism that humanitarian work would face. Over the years, the Red Cross has been accused of legitimizing war by trying to regulate it, of condoning war and even of making war more acceptable by committing to saving its victims.

Nevertheless, the Red Cross has remained faithful to the approach of tackling the consequences of war without addressing the causes. It has taken this approach consistently, even though Gustave Moynier's optimistic prediction has not been borne out: countries have in no way refrained from going to war because of the Red Cross' efforts to increase awareness of the suffering of wounded soldiers and the humanitarian consequences of war. When countries go to war, they either believe they will be victorious or they see no alternative, or they simply view war as the continuation of diplomacy by other means.

The debate has not fundamentally changed, not as more and more civilians become victims of modern warfare and not as States have undertaken to care for victims more systematically.

It is true that for the better part of a century, the Red Cross limited itself to playing the role of Good Samaritan, healing the wounds of war without attempting to prevent conflict.

Preventing war was a political issue, the responsibility of the United Nations and States. The Red Cross felt it could not get involved without compromising its neutrality and thereby its capacity to help the victims should war break out anyway.

But with the arrival of modern warfare and weapons of mass destruction – and the increasingly dire consequences for civilians – this attitude no longer held up. The use of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of the Second World War and the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 marked a turning point. The push for nuclear disarmament after 1945 is well known. But to understand why it was a defining moment for the pursuit of peace and for neutrality in humanitarian work, it is worth recalling the causes of the Cuban Missile Crisis in broad terms.

On Sunday, 14 October 1962, two American U-2 spy planes flying over Cuba took photos which showed that the Soviets were building launch pads capable of carrying nuclear missiles.

In a televised speech on Monday, 22 October 1962, President Kennedy revealed the existence of Soviet bases in Cuba to the American people and the world, to general astonishment. He said that it was a threat to the United States and the whole American continent that could not be tolerated. He announced that to prevent Soviet missiles from reaching Cuba, the US Navy would intercept all ships within 800 kilometres of the easternmost point of the island.

This crisis – for the first and last time in history – saw the United States and the Soviet Union confronting each other directly regarding their nuclear armaments. The two countries recalled their reservists and put their strategic forces on maximum alert. As Soviet ships were en route for Cuba, the US Navy was preparing to intercept them. The whole world held its breath.

The United Nations secretary-general, U Thant, started mediation, but he quickly came up against the question of control of the ships on their way to Cuba. During the night of 29 to 30 October, he called the ICRC president, Léopold Boissier, to appeal for the ICRC's support. He said that the Soviets and the Americans wanted control of the ships to be given to the ICRC, which, in their eyes, provided the best guarantee of impartiality.

This appeal left the ICRC with a critical choice. On the one hand, it was clear that controlling ships on the high seas, as requested by the United Nations, and thereby Washington and Moscow, fell outside the ICRC's traditional mandate. On the other hand, it seemed irresponsible to refuse to assist when world peace and the survival of humanity were at stake.

Mr Boissier convened an extremely secret extraordinary meeting of the Committee. So as not to arouse suspicion, they met at a very exclusive club in Geneva's old town, Le Cercle de la Terrasse. The members were divided. Some were concerned that, by accepting the extremely political mandate that the United Nations wanted to give it, the ICRC would compromise its neutrality and ability to continue saving victims of war. Others highlighted the moral impossibility of refusing to assist when humanity was faced with the risk of nuclear war. Mr Boissier recalled the Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross, adopted a year earlier, which state that "the Red Cross (...) promotes mutual understanding, (...) cooperation and lasting peace amongst all peoples".

One argument carried the decision. Professor Schindler, a leading specialist in international law, noted that were the Cuban Missile Crisis to lead to nuclear war, the ICRC would in any case be unable to carry out its humanitarian mission. His reasoning was based on the experiences of Marcel Junod in Hiroshima in 1945. That tipped the scales, and the ICRC decided to accept the United Nations' request.

In the end, the ICRC did not have to carry out the United Nations' mandate, but the step had nevertheless been taken. When the world was threatened by nuclear war, the ICRC had agreed to provide its services with the aim of helping prevent a conflict that would have threatened the survival of humanity.

It was up to the 20th International Conference of the Red Cross, held in Vienna in 1965, to learn from this event. It retrospectively approved the ICRC's decision, encouraging the organization "to undertake, in constant liaison with the United Nations and within the framework of its humanitarian mission, every effort likely to contribute to the prevention or settlement of possible armed conflicts, and to be associated, in agreement with the States concerned, with any appropriate measures to this end."

Despite the exceptional circumstances that motivated it, the ICRC's decision in the Cuban Missile Crisis created a precedent. Since then, the ICRC has offered its services several times, to: prevent conflicts from escalating further, contribute to ending a conflict, or resolve humanitarian issues between the parties to conflict, through trust-building measures and peace talks.

Examples include:

- The conflict in southern Lebanon in 1982, when Israeli armed forces were preparing to chase Palestinian combatants out of southern Beirut, where they were entrenched, even if it meant bloody street battles. Negotiations carried out under the auspices of the United States led to an agreement for the peaceful evacuation of the Palestinian combatants. The ICRC was invited to contribute to the implementation of this agreement. It agreed in the interests of preventing an assault on the Lebanese capital, which would have led to a bloodbath and terrible loss of civilian life. However, as the Palestinian combatants insisted on withdrawing with their weapons, the ICRC could not supervise their evacuation and instead focused on evacuating injured people. This was done by sea, in two operations using a hospital ship chartered by the German Red Cross.

- During the last phase of the awful civil war that tore apart El Salvador between 1979 and 1990, the ICRC organized several meetings between representatives of the government of El Salvador and representatives of the insurgency, with the aim of reaching agreements for releasing prisoners. The parties to the conflict used these meetings to carry out political negotiations that led to a ceasefire and the end of the civil war.

- The occupation of Kuwait in August 1990 caused a crisis between Iraq and a large coalition led by the United States. The ICRC proposed a series of measures with a view to resolving the situation. They were mainly humanitarian measures, such as ensuring access to Kuwait and to western hostages held by the Iraqi government An agreement was about to be signed when Saddam Hussein vetoed it. Everyone knows what happened next.

- During the Chiapas conflict, which devastated this large region of southern Mexico in spring 1994, the ICRC was called on not only to organize meetings between representatives of the Mexican government and the Zapatist insurgency, but also to help organize elections, which were an essential requirement of the insurgency for ending the conflict. Although organizing elections clearly fell outside the ICRC's traditional mandate, the ICRC agreed to do it to broker peace in the region.

- Finally, in Cuba, the ICRC and the facilitator States helped with the arrangements for several sessions of negotiations between representatives of the Columbian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP). Thanks to these negotiations, a ceasefire agreement was reached that put an end to the clashes that had been tearing Columbia apart for over half a century.

These precedents have given the ICRC practical experience in conflict prevention and resolution in areas that are, depending on the case, more or less closely related to humanitarian issues.

Today the ICRC is fulfilling more than 30 different requests to act as a neutral intermediary in conflict. We are called on to prevent relations from deteriorating, prevent conflicts from escalating, or to find mutual trust-building measures that would help advance the peace process. These actions can be periodic or regular, but in no way do we intend to stand in for the political institutions, which are the United Nations and the regional organizations. Rather, we draw on our humanitarian experience to arrive at a more substantive peace process, led by States and international organizations. Clearly, the ICRC's work is not the same as it was in the early years.

Today we are more concerned with preventing conflicts, or at least preventing them from deteriorating because of the growing impact they have on civilians. Cities are the new battlefields, with undeniable consequences in terms of blind violence. Wars are becoming more protracted and complex. And underdevelopment, violence, corruption and lawbreaking have weakened many societies. All these factors intensify the pressure on the ICRC to do more to prevent conflicts.

- It is becoming more difficult to explain our short-term, unconditional, emergency response when humanitarian work is increasingly long term. In our ten largest operations, we have been on the ground for an average of 36 years.

- The people we help are asking us to address all of their various needs. They are finding it harder to accept that their needs are separated into categories: humanitarian, development, peace and human rights.

- Donors and people living in donor countries are getting tired of supporting the same humanitarian work over again each year, with no end in sight.

- Humanitarian work needs to be more than a temporary effort to meet a specific need of the victims. A more comprehensive approach must be taken to deal with the breakdown in the social support, health-care, water-supply and infrastructure networks that are often destroyed in armed conflict. In line with changing needs, humanitarian work now more often bolsters support structures to stabilize societies and facilitate peace.

- Neutral, impartial and independent humanitarian action remains indispensable when taking a consensus-based approach in war and complex situations of violence. However, the sheer scale of people's needs forces us to position our emergency work within the framework of a long-term response, individuals in the framework of the wider population, and humanitarian work in the framework of peace and development.

These efforts are no substitute for political action; nor could they become political, development or human-rights work. But in today's world, humanitarian work must increasingly be seen as a building block for peace.

People's needs are the basis for all humanitarian work, and those needs are undergoing a profound change. It would be impossible, today, to limit humanitarian work to health care, water and shelter and a strict interpretation of international humanitarian law. We must acknowledge that people's need for peace, development and human rights are needs that an organization such as ours cannot ignore. Humanitarians take a different, much more consensus-based approach to these needs. But peace remains the ultimate goal of neutral and impartial humanitarian work, and that goal is highly political.

In conclusion, I would like to point out that the ICRC was created to encourage the foundation in countries around the world of societies to aid wounded soldiers – the future National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies – and to push for the adoption of a treaty protecting the wounded and military health services on the battlefield. We were created with a humanitarian aim and have always remained faithful to our primary purpose, even if the founding fathers held out a vague hope for peace in their societies.

The changing face of war and the shift in people's needs have led us to accept a pragmatic extension to our mandate on a case-by-case basis, with the aim of: preventing a nuclear war that could end humanity, implementing political agreements with a humanitarian component, building the trust needed to begin peace processes, etc. The ICRC has always been willing to respond to requests from the international community, provided there is consensus on all sides. These actions were considered at the International Conference of the Red Cross in 1965, which encouraged the ICRC to take similar initiatives should the circumstances that led to its initial involvement occur again.

The ICRC's competence in conflict prevention has been established by a long chain of precedents, with the understanding that primary responsibility in this area lies with the States and the United Nations. The ICRC has all the more reason to be involved today, given how drawn out conflicts are becoming and how profound an impact they are having on civilians.

The ICRC's involvement is nevertheless subject to specific limitations. I will mention three of them:

- First, it is clear that the ICRC must not do anything that may weaken the United Nations' authority. Primary responsibility for prevention and resolution of international conflicts lies with the United Nations.

- Second, because of the principles of neutrality and impartiality that guide our actions, the ICRC can only act upon the request of or with the agreement of all interested parties. This means that under no circumstances could we participate in negotiations aiming for separate peace since separate peace is not peace but rather a political manoeuvre and an act of war. There must be a solid consensus in favour of our involvement before we can get involved in peace processes.

- Finally, it is clear that the ICRC must not take any action in the area of prevention of conflicts that may endanger our humanitarian mission or our ability to help the victims of war, should our efforts to avoid a conflict fail.

These limitations are important. But within this framework, the ICRC can work with a view to either preventing a conflict likely to break out, or to ending a conflict.

We have valuable assets for this:

- Our role as a neutral intermediary, which has been recognized since the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

- The Fundamental Principles that have guided our actions since our work began, particularly the principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence, which also guide our work in conflict prevention.

- The network of National Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, which, thanks to its close ties to the local populations, allows us to understand people's needs.

- Finally, Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, which authorizes the ICRC to offer its services to both the governmental and the insurgent parties to non-international armed conflicts. Because the ICRC is not an intergovernmental organization, this offer of service and any contacts that the ICRC makes on this basis do not affect the legal status of the parties to the conflict. This means we can act where others cannot.

The ICRC has taken many initiatives in recent decades in a growing number of conflicts, either alone or in cooperation with the United Nations or one or more facilitator States. These initiatives show that the ICRC has developed a philosophy of humanitarian work as contributing to peace. More generally, humanitarian action is fundamentally an act of peace during combat.

Today, 8 June 2017, we are celebrating the 40th anniversary of the adoption of the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions, which updated not only the rules protecting the victims of war but also those governing the conduct of hostilities. On this day, I would not want to conclude without reiterating the fact that the ICRC is available to all States and all parties involved in armed conflicts or other situations of violence, not only to carry out our humanitarian mandate, but also to work to maintain or restore peace under the conditions that I just mentioned.