It is a great privilege to be joining you on this auspicious occasion to mark the 150th anniversary of the St. Petersburg Declaration. I would like to thank our partners from the Interparliamentary Assembly of the CIS, Chairperson Mme Matvienko, and Secretary General Mr Osipov, for co-organizing this very important event and for your long-standing cooperation.

The ICRC has enjoyed a positive and productive relationship with the IPA for more than 20 years, especially on developing and strengthening the implementation of international humanitarian law.

In particular the ICRC has welcomed the adoption of a series of model laws and recommendations on IHL by the Assembly and we look forward to ongoing engagement.

I would also like to thank the distinguished participants from the CIS Member nations and countries who historically signed the St Petersburg Declaration as well as those from countries beyond the ratification scope for your participation in this Conference.

The face of war has changed radically over the last 150 years.

Then, wars were mostly fought on vast battlefields, with heavy weaponry, pitting large armies against each other in open fields.

Now the frontlines are urban areas – battles often fought in densely populated cities, in neighbourhoods, on the doorsteps of family homes.

Once wars were military to military, now civilians are most likely to die or be injured.

Weapons have transformed – today they are more powerful and more deadly. And new, virtual frontlines are emerging in cyberspace.

Despite these vast differences, the imperative to protect and preserve humanity by setting limits on war remains as true today as it was 150 years ago.

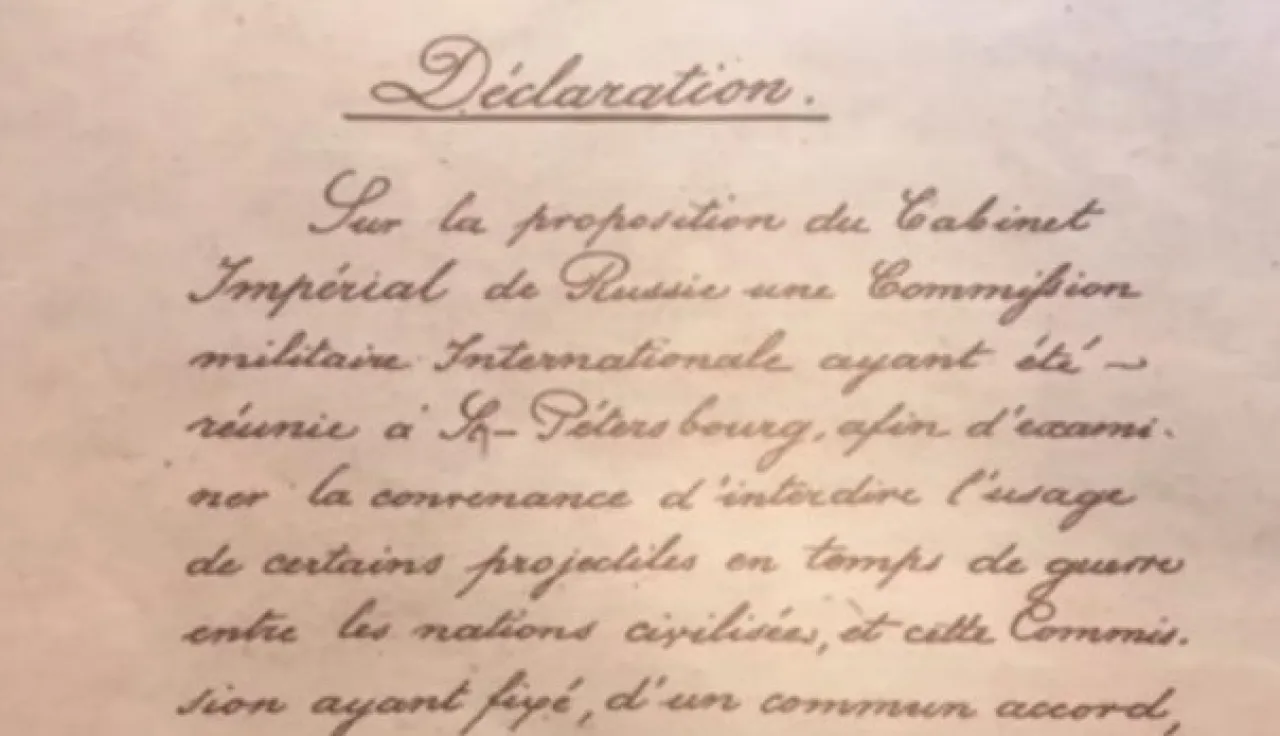

The authors of the 1868 St Petersburg Declaration were alive to this necessity. They set limits not only to prohibit a new weapon but also to reaffirm the humanitarian principles applicable to warfare, and as they described: "the necessities of war ought to yield to the requirements of humanity".

The Declaration was ground-breaking for the time. It was the first formal multilateral agreement to prohibit the use of a weapon in war – exploding bullets – deemed to be too cruel. And further, it was pre-emptive: banning a weapon before it had even been used.

The Declaration is also remarkable for how it came about: it was adopted by military powers convened by Russia to prohibit a new weapon that it had itself developed but which, it had concluded, was morally unacceptable.

And it built and left a legacy: from early efforts to the inter-war period of the 20th century, to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the disarmament treaties that followed the Second World War, the Petersburg Declaration has been a visionary approach to inspire agreements.

Today, all rules of international humanitarian law that protect the most vulnerable in armed conflict embody the careful balance between military necessity and humanity that was evoked by the St Petersburg Declaration.

This point is a critical reminder for us today: international humanitarian law is a pragmatic body of law, which has already taken military needs into account.

The Declaration shows us too, the positive power of how States can take responsible action, leading from the front with the courage to uphold principles of humanity.

This positive example is sorely needed in today's world, especially as we see the deep transformation of the dynamics of conflict and rising humanitarian needs.

In conflicts around the world the ICRC sees more people affected, for a longer time, with deeper basic needs, ranging from food, water and shelter, to health care and economic opportunities.

Today, conflicts and protagonists cross State borders. Conflicts are protracted. Battles are fought in populated areas, risking too many civilian lives and destroying critical infrastructure.

A vast array of armies, Special Forces, armed groups, and criminal gangs now fight – directly or by proxy, openly or secretly. Civilians by day may become fighters at night, spreading doubt on applying the principle of distinction.

The sheer number of groups has rapidly increased too - ICRC research shows more armed groups have emerged in the last six years than the previous six decades.

Wars today often involve partners and allies – leading to a dilution of responsibility, fragmentation of command chains and an unchecked flow of weapons. Partnering is a risky strategy too for States, rife with political and reputational dangers, for example if their support is redirected or used in violation of IHL.

Additionally the applicability of IHL itself is questioned: whether by armed actors, political actors or otherwise – one is often confronted with scepticism on the significance of the law today, with questions such as: 'The other side does not respect it, so why should we?' 'They are terrorists, so the law does not apply to them.'

Coupled with daily reports of atrocities in conflict zones, this negative discourse can lead to despair and a narrative that casts doubt the impact and relevance of IHL in modern warfare.

But it would be wrong – and indeed dangerous – to believe that international humanitarian law is always violated and is therefore useless. The focus on violations risks to de-legitimize the law over time.

At the same time we must recognize that a gap of compliance remains. While support existing processes, we must also find new ways to ensure greater respect.

Undeniably the formal processes remain important. The ICRC and Switzerland are leading such an effort with States on Strengthening Respect for IHL in the lead up to the 33rd International Conference of the Red Cross Movement next year.

This will be an important moment to reinforce support for international humanitarian law, in a non-political, voluntary and consensus-based way. We have been encouraged by the active participation of states

in the process and we ask that the members of the international community be ambitious in their commitments.

We must also recognize that as the conflict environment changes, we also need to be adapting to new approaches to influence the behaviour of belligerents and increase respect for the law.

The ICRC is mandated to engage with all parties to a conflict and strives to do so with an increasingly complex array of non-state armed groups. Currently we are in contact with around 200 groups worldwide linked to our operations or our humanitarian concerns; and we are discovering that the structure of these groups underscore the necessity for new approaches.

Our innovative new research on the factors that lead to restraint in war has provided us unprecedented evidence on how members of State militaries and non-State armed groups are influenced.

The findings confirm the method of integrated IHL training that the ICRC has pursued for the past 15 years is the right one for vertically structured armed forces and groups.

But for non-state armed groups, a different approach is needed. We have found evidence that decentralised groups are more sensitive about pressure from peers than instructions from superiors; we have seen that the way to positively influence armed groups is dependent on the structure of the group, informal behavioural codes within a group and its interaction within society.

These findings are relevant not only for the ICRC, but also for highly professional armies and for those with whom they are increasingly partnering in different operations around the world.

Dear colleagues

As the trend towards allied and partnered warfare only increases, it has become increasingly urgent for States to look at how they can better leverage their partnerships and support to ensure civilians are better protected.

In partnerships, as in all other cases, the ICRC encourages all States to lead by example: to steadfastly respect their own obligations under international humanitarian law.

We have designed an agenda for action, based on our analysis from the field, which sets out the practical steps States can take to help parties they support behave in ways that comply with the law including:

- Refraining from transferring weapons if there is a clear or substantial risk that they could be used to commit serious IHL violations;

- Vetting potential partners to ensure they have the capacity and willingness to apply IHL; and

- Ensuring proper application of the rules governing the conduct of hostilities, the protection of civilians and of medical facilities and the treatment of detainees.

I have seen the positive impact when allied States put in place such measures and I encourage all States to examine their responsibilities and actions. Indeed, we look forward to constructively furthering this discussion with States over the coming year.

There are many examples of States taking steps to protect civilians and to uphold international humanitarian law. But there are also times, when negotiations fail to make any progress. Many people today speak about the failures of multilateral diplomacy, blocked dialogue and breaches of widely accepted conventions.

The ICRC is a neutral, impartial, independent organization, but we see the impacts on the ground of political impasse. We see people struggling to survive or to hold onto hope as protracted conflicts drag on for decades without a political solution in sight.

We also see the results when weapons are used without limits, without regard for civilian life, when the internationally agreed constraints of distinction, proportionality and precaution are ignored.

And we see the result when these principles are pushed aside and military necessity dominates over concerns for the protection of civilians. Victory may come, but at what price?

ICRC firmly believes that disarmament and arms limitation are not solely tools to maintain international peace and security, and to prevent or end armed conflict. They are also critical means to mitigate the impact of armed conflict when it occurs.

I will highlight three key areas of concern:

One, the use of explosive weapons: In the ongoing armed conflicts in Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Ukraine and beyond the ICRC is seeing the disastrous consequences of heavy explosive weapons used in densely populated areas.

When a city is shelled the consequences are not limited to death, physical injury, but also include damage to critical infrastructure such as water and electrical facilities, hospitals and health services.

Given the enormous civilian costs, the ICRC calls on all parties to avoid the use of explosive weapons with wide-area effect in populated areas, due to the significant likelihood of indiscriminate effects.

Two, on nuclear weapons. The ICRC, as part of the broader International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, has long advocated for the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons.

Our call is rooted in our first-hand observation of the horrific consequences of the atomic bombings in 1945, and the evidence that even the limited use of nuclear weapons would have devastating, long-lasting and irreparable humanitarian consequences. The only realistic means of safeguarding against nuclear catastrophe is nuclear disarmament.

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is an essential building block toward fulfilling existing commitments for nuclear disarmament, in particular those in Article VI of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which it complements. In addition, the ban on nuclear weapons supports the NPT's non-proliferation objectives.

If nuclear-armed States are unable at this time to join the treaty, we implore them to take urgently needed measures to reduce the risks of intentional or accidental use of nuclear weapons, as they have long promised to do.

Three, on cyberspace. In the ICRC's view, it is clear to us that the general rules of international humanitarian law apply to and restrict the use of cyber capabilities as means and methods of warfare during armed conflicts.

IHL prohibits cyber-attacks against civilian objects or networks, and prohibits indiscriminate and disproportionate cyber-attacks.

This is not to deny that new or more tailor-made rules might be useful or even needed as technologies evolve and their humanitarian impact is better understood.

Indeed, the interconnectedness of military and civilian networks poses a significant practical and legal challenge in terms of protecting civilians from the dangers of cyber warfare. If new rules are developed, it is important that they build on and strengthen what already exists.

Additionally, given the significant interest of militaries in autonomous weapons, there is a growing risk that humans will become so far removed from battlefield choices that life-and-death decision-making is effectively left to sensors and software.

Human control must be maintained over weapon systems and the use of force. States need to seriously engage to find a common understanding on the level of human control, which should guide future weapon's systems. We also need limits on autonomy, which satisfy both ethical and legal considerations.

As the St Petersburg Declaration demonstrated in pre-empting the deadly consequences of a new weapon, it is vital that we prevent unacceptable harm before it occurs.

I understand that many of the themes I have mentioned will be discussed during the conference, and I encourage you to deliberate and debate the issues to further our shared understanding.

The ICRC as the reference organization on IHL, and with its practice embedded deep within field realities, is ready to assist you to find solutions.

Dear colleagues

Today, as we mark this special anniversary, I invite you to take inspiration from the authors of the Declaration, who sought a pragmatic balance between military necessity and humanitarian principles.

By exercising responsible leadership collectively, taking bold initiatives, reaching out to adversaries and competitors, we can progress on fulfilling long-standing disarmament commitments, on upholding international humanitarian law, and safeguarding peace and security.

Speech given by the Peter Maurer, ICRC President at the International Conference: "150th Anniversary of the Declaration Renouncing the Use, in Times of War, of Certain Explosive Projectiles: New Context, Undiminished Relevance" St Petersburg, 30 November 2018