Frequently asked questions on the rules of war

Even wars have rules. What does that mean?

It means: You do not attack civilians. You limit as much as you can the impact of your warfare on women and children, as well as on other civilians. You treat detainees humanely. You do not torture people.

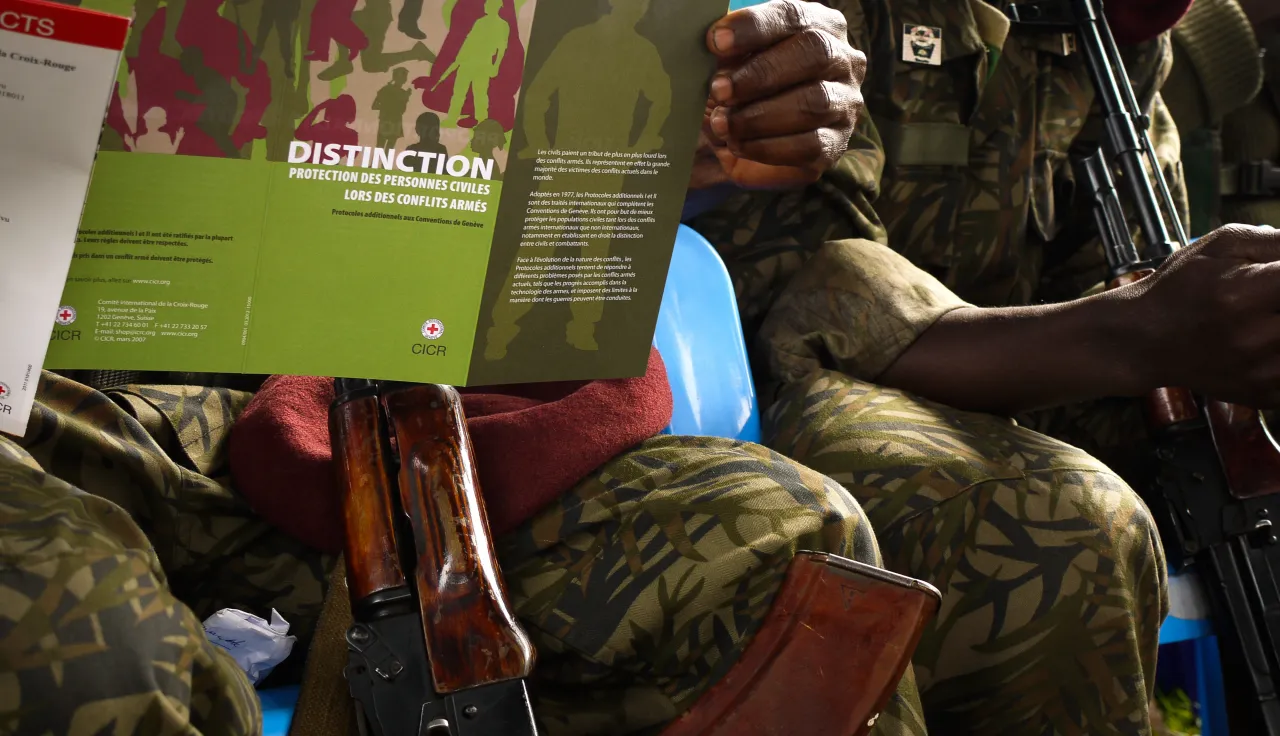

International humanitarian law: what are we talking about?

International humanitarian law (IHL) is a set of rules that seeks, for humanitarian reasons, to limit the effects of armed conflict.

It protects persons who do not, or no longer, take part in the fighting (including civilians, medics, aid workers, wounded, sick and shipwrecked troops, prisoners of war or other detainees), and imposes limits on the means and methods of warfare (for instance, the use of certain weapons).

IHL is also known as 'the law of war' or 'the law of armed conflict'. IHL is made up of treaties (the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols are the main ones) and customary international law.

When does IHL apply?

IHL applies only in situations of armed conflict. Apart from a few obligations that require implementation in peacetime (e.g. adopting legislation, teaching and training on IHL) it does not apply outside of armed conflict. IHL offers two systems of protection: one for international armed conflict and another for non-international armed conflict. IACs are armed conflicts among two or more States.

NIACs involve governmental armed forces fighting against one or more non-state armed groups, or such groups fighting each other. The rules that apply depend on whether a situation is an international or non-international armed conflict. Some rules of IHL continue to protect victims of armed conflicts even after they have ended (eg. detainees or missing).

Who is bound by IHL?

IHL is universal: all parties fighting in a conflict are obliged to respect IHL, be they governmental forces or non-State armed groups. The Geneva Conventions, which are central to IHL, have been ratified by all 196 States, making IHL a universal body of law. Very few international treaties have gained this level of support.

They are complemented by the two Additional Protocols from 1977, the first one regulating international armed conflicts and the second one non-international armed conflict, as well as the Third Additional Protocol from 2005, which creates the red crystal emblem alongside the red cross and the red crescent.

Today, 174 States are party to Additional Protocol I, 169 to Additional Protocol II and 79 to Additional Protocol III. Alongside treaties, customary law can fill gaps where treaties are not applicable or where treaty law is less developed, as is the case for NIAC. Customary rules bind all parties to armed conflict.

Who are prisoners of war?

In a nutshell, prisoners of war are combatants who have fallen into enemy hands in an international armed conflict. Combatants can be members of the regular armed forces, as well as militia, volunteers or other such groups if they belong to a party to the conflict and fulfil certain conditions.

A small number of non-combatants, such as medics, journalists, supply contractors, and civilian crew members, are also entitled to prisoner-of-war status when they are affiliated with or have special permission to accompany the armed forces. There is also a possibility for civilians who spontaneously take up arms in a 'levée en masse' to be prisoners of war. POW status is regulated by the Third Geneva Convention and Additional Protocol I.

What kind of treatment are POWs entitled to?

Throughout their internment, POWs must be treated humanely in all circumstances. They are protected against any act of violence, as well as against intimidation, insults, and public curiosity. IHL also defines minimum conditions of internment for POWs, addressing issues such as accommodation, food, clothing, hygiene and medical care.

POWs cannot be prosecuted for having taken a direct part in hostilities, but they may be prosecuted for possible war crimes. Their internment is not a form of punishment but only aims to prevent them from further participation in the conflict. POWs must be released and repatriated without delay after the end of active hostilities.

During international armed conflicts, the ICRC has a right to visit prisoners of war to make sure that their treatment and the conditions in which they are being held are in line with IHL.

What about civilians deprived of their liberty? Does IHL protect them?

During armed conflict, civilians might also be deprived of their liberty. IHL only allows for the internment of protected civilians if it is absolutely necessary for the security of the party detaining them. Internment may never be used as a form of punishment. This means that internees must be released as soon as the reasons that made it necessary to intern them no longer exist.

The person must be informed why they are interned and must be able to challenge the decision to intern them. IHL also sets out minimum conditions of detention, covering such issues as accommodation, food, clothing, hygiene and medical care. Civilian internees must be allowed to exchange news with their families. Civilian internees must be treated humanely in all circumstances.

IHL protects them against all acts of violence, as well as against intimidation, insults, and public curiosity. They are entitled to respect for their lives, their dignity, their personal rights and their political, religious and other convictions. During international armed conflicts, the ICRC has a right to visit civilian internees to make sure that their treatment and the conditions in which they are being held are in line with IHL.

What protection does IHL afford to the wounded, sick or shipwrecked?

The wounded and sick include anyone in an armed conflict, whether military or civilian, who needs medical attention and is not taking part in hostilities. All wounded, sick or shipwrecked persons, no matter what party they belong to, must be respected and protected.

The wounded and sick must be respected and protected in all circumstances. This means that they may not be attacked, killed or ill-treated, and that the parties must take steps to help them and protect them from harm. Parties to the conflict have to take all possible measures to search for and collect the wounded and sick. Put simply, parties to conflict must also provide the best possible care as quickly as possible.

Only medical reasons can authorize priority in treatment. For international armed conflicts, the treatment of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked is set out extensively in the First, Second and Fourth Geneva Conventions, the First Additional Protocol as well as customary rules. For non-international armed conflicts, it is set out in Common Article 3, the Second Additional Protocol and customary rules.

What do parties to armed conflict have to do about people who go missing? And for the dead?

Under IHL, parties to armed conflicts have to prevent people from going missing or being separated from their loved ones. In the case people do go missing, parties to conflicts must work to clarify their fate and whereabouts and communicate with the families. In preventing people from going missing and being separated from their families, communication is key.

For instance, IHL requires parties to an armed conflict to register persons deprived of their liberty and allow them to correspond with their families. They must also record all available information relating to the dead and ensure that the management of human remains is carried out in a dignified manner. During international armed conflicts, the parties must also use their National Information Bureaus to collect information on all protected persons who find themselves in their hands, dead or alive, and transmit that information to the Central Tracing Agency.

Parties to an armed conflict must take all feasible measures to account for the missing, the separated and the dead, provide family members with information, and facilitate the restoration of family links. This involves searching for, collecting and evacuating the dead and facilitating the return of human remains to families upon request. Some IHL obligations regarding the missing continue even after the conflict has ended.

What if there is an occupation? What protections apply?

Under IHL, an occupation is a form of international armed conflict. An occupation occurs when the territory of a State is actually placed under the authority of a hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.

When a State consents to the presence of foreign troops, there is no occupation. In addition to the general protections afforded to the civilian population, civilians living in occupied territory are entitled to specific protection which aims to prevent abuses by the occupying power. These protections are set out in Section III of the Fourth Geneva Convention and in the 1907 Hague Regulations, as well as in customary law rules.

In general terms, occupation law strikes a balance between the security needs of the occupying power on the one hand, and the interests of the ousted power and the local population on the other. The occupying power's responsibilities include matters such as management of public properties, functioning of educational establishments, ensuring the existence and functioning of medical services, allowing relief operations to take place as well as allowing impartial humanitarian organizations such as the ICRC to carry out their activities.

In turn, the occupying power also has certain rights, which may take the form of measures of constraint over the local population when necessity so requires.

What does IHL say about refugees and internally displaced persons?

Refugees are people who have crossed an international border due to a well-founded fear of persecution in their country of origin. People can become refugees for many different reasons, including reasons related to armed conflict.

IHL protects refugees in particular when they find themselves in a territory where armed conflict is taking place. In addition to the general protections afforded to the civilian population, refugees are entitled to certain specific protections in international armed conflicts.

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) are persons who have not crossed an international border but have been forced to flee their homes. IDPs enjoy the general protections afforded to all civilians. In addition, specific IHL rules require that, in case of displacement, all possible measures be taken to provide satisfactory conditions of shelter, hygiene, health, safety and nutrition and that members of the same family are not separated.

When duly respected, IHL rules can also help prevent displacement, for example by prohibiting starvation of the civilian population and destruction of objects indispensable to its survival. IHL prohibits forced displacement unless the security of civilians or imperative military reasons so demand.

How does IHL protect women?

In armed conflict, women can be victims, fighters, bystanders, and actors of influence. They enjoy the general protections afforded to the civilian population or to combatants, according to their status. IHL prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex or gender. Women are also put at risk by the constraints that are imposed on them, and are disproportionately impacted by certain kinds of violence, including sexual violence.

IHL addresses these risks, including by prohibiting rape, enforced prostitution or any form of indecent assault against all persons. Violations of these prohibitions may amount to war crimes. In addition, IHL provides for specific treatment of female POWs and civilian internees, as well as pregnant women.

Their specific protection, health and assistance needs must be respected. For example, women, men, boys and girls of different ages and backgrounds can have different medical needs, and can be exposed to different risks hindering equal care. It is important to take the perspectives of women and men from different ages and backgrounds into account.

How does IHL protect children?

Children are especially vulnerable in armed conflicts. Their needs also depend on factors such gender, socioeconomic status and disability. Children enjoy general protection as civilians under IHL, and also benefit from special protections.

For example, they must be given age-appropriate access to food and health care, and steps must be taken to facilitate their continued access to education. IHL also prohibits the recruitment of children into the armed forces or armed groups, and parties must not allow them to take part in hostilities.

The age of lawful voluntary and compulsory recruitment depends on the treaties a State is party to. Notably, most States are party to the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, which sets the age of compulsory recruitment and direct participation in hostilities at age 18. This instrument also entitles unlawfully recruited children to assistance for their physical and psychological recovery and their social reintegration.

Some State have endorsed the Paris Commitments and Principles on Children Associated with Armed Forces and Armed Groups, which provides further guidance on the treatment and reintegration of unlawfully recruited children.

Does IHL protect people with disabilities?

Yes. Of course, when they are civilians or people hors de combat, people with disabilities benefit from all general protections under IHL. In addition, already in 1949, the drafters of the Geneva Conventions recognized that people with disabilities needed specific protection during armed conflict.

IHL requires parties to armed conflicts to give special respect and protection to persons with disabilities, such as in rules relating to internment, as well as evacuations from besieged or encircled areas. Contemporary understandings of IHL and of the rights of people with disabilities highlight the specific needs and barriers they may face, as well as the particular risks to which they are exposed in an armed conflict environment.

These specific barriers and risks should also be factored into the interpretation of IHL rules on the conduct of civilians, such as obligations to take feasible precautions.

Does IHL contain rules on torture?

Yes. Torture and other forms of ill-treatment are absolutely prohibited everywhere and at all times. Both IHL and international human rights law (IHRL) complement each other in creating a comprehensive body of rules for the prevention and punishment of acts of torture and other forms of ill-treatment.

States have agreed that there can be no excuse for torture. The suffering caused by such practices may have profoundly disturbing effects on victims that can last for years.

What are the main principles governing the conduct of hostilities?

The IHL rules on conduct of hostilities aim to strike a balance between military necessity and humanity, seeking mainly to protect civilians from attacks and the effects of hostilities. Principle of distinction: Parties to an armed conflict must "at all times distinguish between the civilian population and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives and accordingly shall direct their operations only against military objectives".

IHL prohibits attacks directed against civilians, as well as indiscriminate attacks, namely those that strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction. Principle of proportionality: IHL prohibits attacks that may be expected to cause excessive incidental civilian harm in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated. In the conduct of hostilities, causing incidental harm to civilians and civilian objects is often unavoidable.

However, IHL places a limit on the extent of incidental harm that is permissible by spelling out how military necessity and considerations of humanity must be balanced in such situations. Principle of precaution: In the conduct of military operations, constant care must be taken to spare the civilian population, civilians and civilian objects. All feasible precautions must be taken to avoid, and in any event to minimize, incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects.

Given the significant risk of harm to civilians whenever the military is executing an attack, IHL imposes detailed obligations to those planning, deciding on or carrying out attacks. It also requires parties to the conflict to protect civilians and civilian objects under their control against the effects of attacks.

Specific protection: Various types of persons and objects enjoy additional, specific protection. For instance, particular care must be taken to avoid the release of dangerous forces and consequent severe losses among the civilian population if dams, dykes and nuclear plants and other installations located in their vicinity are attacked.

Even more stringent restrictions are imposed when the 1977 First Additional Protocol applies. Specific protection is also afforded to medical personnel and facilities; humanitarian personnel and activities; the environment; goods indispensable to the survival of the civilian population; cultural property.

Do civilians picking up arms lose their protection against direct attack under IHL?

It depends. IHL defines civilians as anyone who is neither a member of State armed forces, nor a member of an organized armed group with a continuous combat function, nor a participant in a levée en masse.

Civilians are protected against direct attack unless, and for such time, as they directly participate in hostilities. Parties to an armed conflict must take all feasible precautions in determining whether a person is a civilian and, if that is the case, whether he or she is directly participating in hostilities.

In case of doubt, the person in question must be presumed to be a civilian and protected against direct attack. To protect civilians, combatants – and anyone directly participating in hostilities – must distinguish themselves from civilians in all military operations by wearing identifiable insignia and carrying arms openly. The ICRC has issued Interpretive Guidance which provides recommendations concerning the interpretation of IHL as it relates to the concept of direct participation in hostilities.

Can parties to a conflict use any kind of weaponry to attack or defend themselves?

No, they cannot. From the beginning, IHL tried to limit the effects of armed conflicts. To this end, IHL imposes limits on the choice of weapons, means and methods of warfare through general rules and through specific rules limiting or prohibiting the use of certain weapons that cause unacceptable harm.

General rules that impose limits on the choice of weapons, means and methods of warfare include the prohibition of weapons which are by nature indiscriminate, and the principles and rules governing the conduct of hostilities, which primarily protect civilians, and the prohibition of weapons which are of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering, which also protect combatants.

Since the 1860s, States have agreed to prohibitions or limitations of certain weapons owing to their actual or potential human cost. These include prohibition on exploding or expanding bullets (1868), expanding bullets (1899), poison and asphyxiating gases (1925), biological weapons (1972), chemical weapons (1993), munitions using undetectable fragments (1980), blinding laser weapons (1995), anti-personnel mines (1997), cluster munitions (2008), nuclear weapons (2017), as well as limitations on the use of incendiary weapons (1980), anti-personnel- and anti-vehicle landmines, booby-traps and other devices (1980 & 1996), and obligations related to explosive remnants of war (2003).

Many of these weapons are today also prohibited under customary law. All weapons, even those not specifically regulated, must comply with the general rules of IHL regarding the conduct of hostilities.

When developing or acquiring a new weapon, States must carry out a legal review to determine whether its use might be prohibited by international law in some or all circumstances. Last but not least, consideration should be given to whether the use of weapons, means or methods of warfare accord with the principles of humanity and the dictates of public conscience.

Why is the ICRC calling on parties to conflicts to avoid using explosive weapons with wide area effects in urban settings?

Explosive weapons with wide-area effects (such as large bombs and missiles, unguided artillery and mortars, and multi-barrel rocket launchers), when used in urban or other populated areas, have grave humanitarian consequences even when directed at military objectives.

These include not only the direct effects of such use (death and injury of civilians, destruction of civilian objects), but also the indirect or 'reverberating' effects (e.g. the disruption of essential services caused by damage to or destruction of critical infrastructure). Because of their large explosive force or lack of accuracy, and the likelihood that their effects will go significantly beyond the target, it is very challenging to use such weapons in populated areas in compliance with IHL.

Explosive weapons with wide-area effects are inappropriate for use in populated areas. Since 2011, the ICRC has been calling on States and all parties to armed conflicts to avoid using such heavy explosive weapons in urban and other populated areas, due to the significant likelihood of indiscriminate effects and despite the absence of an express legal prohibition for specific types of weapons.

This call has also been made by the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement as a whole, the UN Secretary-General and several States and international and civil society organizations.

An 'avoidance policy' means that explosive weapons with a wide-impact area should not be used in populated areas unless sufficient mitigation measures are taken to limit the wide-area effects of the weapon and the consequent risk of civilian harm. These measures, in the form of guidance and 'good practice', should be put in place well in advance of military operations and faithfully implemented when hostilities are conducted in populated areas. Interested in more details? Look at our video and reports here.

What about arms transfers to parties to an armed conflict?

The widespread availability and poorly regulated or controlled transfer of arms and ammunition has a severe human cost. It facilitates violations of IHL, hampers the delivery of humanitarian assistance, contributes to prolonging armed conflicts and maintaining high levels of insecurity and violence even after armed conflicts have ended.

States must refrain from transferring weapons if there is a clear risk that these would be used to violate IHL. States that supply weapons to a party to an armed conflict must do everything reasonably in their power to ensure that the arms recipient respects IHL, for example through risk mitigation measures, conditioning or suspending arms deliveries, or cancelling future ones.

In addition, States parties to the Arms Trade Treaty must assess, before authorizing an export, whether the recipient is likely to use supplied arms, ammunition/munitions or parts and components, to commit or facilitate a serious violation of IHL or human rights law.

If there is an overriding risk of this happening, the export must not be authorized. Under IHL, a State does not become a party to an armed conflict on the sole ground that it supplies weapons or military equipment to a belligerent.

If armed forces are using a hospital or school as a base to launch attacks or store weapons, are those places then a legitimate military target?

The laws of war prohibit direct attacks on civilian objects, like schools. They also prohibit direct attacks against hospitals and medical staff, which are specially protected under IHL. That said, a hospital or school may become a legitimate military target if it contributes to specific military operations of the enemy and if its destruction offers a definite military advantage for the attacking side.

If there is any doubt, they cannot be attacked. Hospitals only lose their protection in certain circumstances - for example if a hospital is being used as a base from which to launch an attack, as a weapons depot, or to hide healthy soldiers/fighters. And there are certain conditions too.

Before a party to a conflict can respond to such acts by attacking, it has to give a warning, with a time limit, and the other party has to have ignored that warning. Some States have endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration and Guidelines, which aim to reduce the military use of schools.

Why should we worry about attacks on cultural property in armed conflict?

Historic monuments, works of art and archaeological sites – known as cultural property – are protected by IHL. Attacks against them are more than the destruction of bricks, wood or mortar – they are, in essence, attacks on our history, our dignity and our humanity.

The rules of war oblige parties to an armed conflict to protect and respect cultural property. According to IHL, attacking cultural property or using it for military purposes is prohibited, unless required by imperative military necessity. Moreover, parties to the conflict may not seize, destroy or willfully damage cultural property and must put a stop to theft, pillage or vandalism directed against it.

Does IHL protect the environment from the effects of military operations?

Yes. The natural environment is civilian in character. Therefore, any part of the natural environment that is not a military objective is protected by the general principles and rules on the conduct of hostilities that protect civilian objects. This means that the parties are prohibited from launching an attack against a military objective which may be expected to cause excessive damage to the environment.

In the conduct of military operations, all feasible precautions must be taken to avoid, and in any event to minimize, incidental damage to the environment. Lack of scientific certainty as to the effects on the environment of certain military operations does not absolve a party to the conflict from taking such precautions. In addition, IHL affords natural environment-specific protections in certain circumstances.

This includes due regard to the protection and preservation of the natural environment in choosing means and methods of warfare, and the prohibition of using methods or means of warfare that are intended, or may be expected, to cause widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment.

Violating this prohibition may amount to a war crime. Destruction of the natural environment may not be used as a weapon. Interested in more details? See the ICRC Guidelines on the Protection of the Natural Environment in Armed Conflict.

What are the rules on sieges?

Sieges often have grave consequences for large numbers of civilians. In order to protect civilians, there are important rules in IHL. Crucially, civilians must be allowed to evacuate from a besieged area. Neither the besieging force nor the force under siege may force them to remain against their will.

Sieges may only be directed exclusively against an enemy's armed forces and it is absolutely prohibited to shoot or attack civilians fleeing a besieged area. In addition, parties must comply with all the rules governing the conduct of hostilities. Constant care must be taken to spare civilians when putting a city under siege and attacking military objectives in the besieged area.

All feasible precautions must be taken to avoid or minimize incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects. IHL also prohibits starving the civilian population as a method of warfare. At the same time, although temporary evacuations may be necessary, and even legally required, sieges must not be used to compel civilians to permanently leave an area.

If civilians become displaced (because they flee or are evacuated from a besieged area), all possible measures must be taken to ensure that the people in question have adequate shelter, have access to sufficient food, hygiene facilities and health-care provision and are kept safe (including from sexual and gender-based violence), and that members of the same family are not separated. Interested in more details? See our 2019 IHL and the challenges of contemporary armed conflicts report, pp 23 to 25.

Is cyberwarfare subject to rules?

Yes. Cyber operations during armed conflict are subject to the established principles and rules of IHL – they do not occur in a 'legal void' or 'grey zone'. The concern for the ICRC is that military cyber operations, which have become part of today's armed conflicts, can disrupt the functioning of critical infrastructure, emergency and humanitarian response, and other vital services to the civilian population.

IHL limits cyber operations during armed conflicts just as it limits the use of any other weapon, means and methods of warfare in an armed conflict, whether new or old. In particular, civilian infrastructure is protected against cyberattacks by existing IHL principles and rules, including the principles of distinction, proportionality and precautions in attack . Moreover, during armed conflicts, the employment of cyber tools that spread and cause damage indiscriminately is prohibited.

Does IHL provide limits on information or psychological operations?

Information or psychological operations have long been part of armed conflicts. However, with the rapid recent growth of information and communication technology, the scale, the speed, and the reach of information or psychological operations has increased significantly.

The ICRC is concerned about the use of information or psychological operations to cause confusion or harm, to spread fear and terror among populations, or to incite violence.

IHL prohibits certain types of information or psychological operations during armed conflicts, such as threats of violence, the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population; using propaganda in order to secure voluntary enlistment of protected persons in occupied territories; or more generally encouraging IHL violations. Information operations must also comply with the requirement to respect and protect specific categories of actors such as medical personnel and humanitarian relief personnel.

What are the dangers with autonomous weapons?

Autonomous weapons select and apply force to targets without human intervention, meaning that the user does not choose specifically who or what will be struck. The difficulties in anticipating and limiting their effects brings risks for civilians, challenges for compliance with IHL and fundamental ethical concerns for society.

The ICRC has urged States to adopt new legally binding rules that prohibit unpredictable autonomous weapons and those that target humans and to strictly limit the development and use of all others.

[VIDEO EXPLAINER] Interested in more details? See ICRC position on autonomous weapons.

Is humanitarian access to populations in need unconditional?

Although the relevant rules vary slightly depending on the nature of the conflict (international armed conflict other than occupation, occupation, or non-international armed conflict), put simply, the IHL framework governing humanitarian access consists of four interdependent "layers."

First, each party to an armed conflict has to meet the basic needs of the population under its control. Second, impartial humanitarian organizations have the right to offer their services to carry out humanitarian activities, especially when the basic needs of the population are not met.

Third, impartial humanitarian activities carried out in armed conflicts are generally subject to the consent of the parties to the conflict concerned. Even so, consent cannot be denied arbitrarily.

Fourth, once impartial humanitarian relief schemes have been agreed to, the parties to the armed conflict, as well as all States that are not party to the conflict, are expected to allow and facilitate the rapid and unimpeded passage of the relief schemes. They may exercise a right of control to verify that the goods are in fact what they are claimed to be. Interested in more detail? Please see: the ICRC's Q&A and Lexicon on Humanitarian Access.

What is ICRC's view on humanitarian corridors and pauses?

"Humanitarian corridors" are places used by humanitarian personnel, for example, to provide the victims of hostilities with relief or to provide them with a safe passage. Whilst IHL is silent on the notion of "humanitarian corridor", IHL rules governing humanitarian access and activities mentioned above provide a framework of reference.

In addition, parties must remove the civilian population from the area of combat, repatriate the wounded and the sick, transfer the dead, and, unless their protection or imperative military necessity so require, allow civilians to leave the territory.

Any initiative that gives civilians a respite from violence and allows them to voluntarily leave for safer areas is a welcome one. Humanitarian corridors must be well planned, well-coordinated and implemented with the consent of parties on all sides.

However, humanitarian corridors are by definition limited in geographical scope and thus are not an ideal solution. Those engaged in the fighting must ensure that all necessary measures and precautions are taken to protect civilians, and that aid is allowed to reach those in need.

A humanitarian pause is a temporary suspension of hostilities for purely humanitarian purposes that is agreed between the parties to the conflict. It is usually for a specific time and area. "Humanitarian pause" and "humanitarian corridor" are not IHL terms of art. Even so, there are important IHL rules that can frame discussions relating humanitarian pauses and corridors.

Parties to all armed conflicts may make agreements to improve the situation of people affected by conflict and need to be guided by the rules on humanitarian access.

How does IHL deal with food security?

A recurring concern in conflict is acute food insecurity. IHL has important rules that can prevent a situation from developing into an extreme food crisis. For instance, parties to the conflict have the obligation to meet the basic needs of the population under their control.

In addition, IHL specifically prohibits the use of starvation of civilians as a method of warfare – a violation of which may amount to a war crime. Moreover, objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, such as foodstuffs, agricultural areas, crops, livestock, drinking water installations and supplies, and irrigation works, are specially protected.

They may not be the object of an attack, destruction, removal or otherwise be rendered useless. Similarly, respect for other IHL rules can play an important role in preventing food insecurity, such as protection of the environment, limitations on sieges, and access to humanitarian relief.

What happens if a State or individuals violate IHL?

A key aspect of limiting the effects of armed conflicts is compliance with the rules. IHL requires parties to a conflict to prevent and repress serious violations of IHL, and to suppress other violations.

A State responsible for IHL violations must make full reparation for the loss or injury it has caused. In turn, individuals responsible for war crimes must be searched for, investigated and prosecuted. States can enforce the rules through their national legal systems, diplomatic channels or international dispute resolution mechanisms.

War crimes can be investigated and prosecuted by any State or, in certain circumstances, by an international court. The United Nations can also take measures to enforce IHL. For example, the Security Council can compel States to comply with their obligations or establish a tribunal to investigate breaches.

What is a war crime?

Serious violations of IHL are known as war crimes. States must investigate war crimes committed by their nationals or armed forces or on their territory and, if possible, prosecute the suspects. States also have the right to investigate other persons for war crimes in their national courts, irrespective of the nationality of the offender or the place where the violations were committed (universal jurisdiction).

IHL holds individuals responsible for the war crimes that they commit themselves, or order to be committed. In this respect, IHL is complemented by international criminal law, which sets out different modes of individual criminal responsibility. Some war crimes are applicable in all armed conflicts, whilst others are specific to international armed conflicts.

In international armed conflicts, certain war crimes are also known as grave breaches, which give rise to additional obligations for States. For example, the following acts would constitute war crimes in all armed conflicts: Deliberately targeting civilians which are not directly taking part in hostilities; Pillage; Hostage-taking; Making religious or cultural objects the object of attack, provided that they are not military objectives; Torture and other forms of inhumane treatment; Child recruitment; Rape and other forms of sexual violence.

The ICRC is not involved in any way in the collection of evidence for or prosecution of war crimes and may not be compelled by courts to testify in trials.

Who is responsible for responding to IHL violations?

The responsibility to prevent and punish IHL violations belongs primarily to States. IHL requires States to investigate serious violations and, if appropriate, prosecute the suspects. This means that appropriate steps must have been taken to implement the criminal repression of IHL violations into a States domestic criminal law. The ICRC's advisory service on IHL is available, on request, to support states with this process. As a complement to domestic investigations and trials, internationally established criminal justice or investigatory mechanisms, including the International Criminal Court (ICC), may promote greater respect for IHL by ensuring that the most serious crimes do not go unpunished. The ICRC supported states in their work to create the ICC and considers it to be an important tool against impunity.

Does the ICRC take part in war crimes investigations?

The ICRC has a clear and long-established practice of not participating in judicial proceedings or disclosing what we discover in our work. Taking part in investigations or judicial proceedings could seriously compromise the trust we try to establish with all the parties to an armed conflict, and eventually jeopardize our access to the people in need.

However, as the guardian of IHL, the ICRC does recognise the crucial role that investigations and prosecutions play in preventing impunity, enhancing respect for the law, and responding to the suffering of victims of armed conflict. Yet, by taking part in these important processes the unique work of the ICRC would be seriously undermined. This is because warring parties are likely to deny or restrict access of the ICRC, in particular to active conflict zones, prisons and detention facilities, if they believe that an ICRC delegate may be collecting evidence for use in future criminal proceedings.

The ICRC's usual approach to possible violations of IHL is therefore to share what we find directly with the parties to the conflict. These conversations are confidential, which allow us to be direct and frank. But confidentiality does not mean silence or acquiescence. The ICRC's preferred approach is to share information and findings on alleged violations of IHL directly with the party responsible. This practice is grounded in extensive experience in the field and has demonstrated that direct dialogue can yield positive results.

Do you share your findings with the International Criminal Court (ICC)?

The information we collect is not and will not be shared with anyone else, including the ICC. This is recognized in the rules of procedure of the ICC, which enshrined the ICRC's privilege of non-disclosure and exempts our staff from being called as a witness to its proceedings. We do take steps to address these issues, just not with others or in the public domain, but rather directly with the parties to the conflict.

Who may use the emblem of the red cross, red crescent or red crystal, and for what purposes?

The emblems of the red cross, red crescent, or red crystal can be used for two different purposes.

First, the emblem can be used to show that certain people or objects are protected as medical personnel or facilities under IHL (protective use). Military medics and civilian medical personnel, as well as their transports and facilities, are entitled to use the protective emblem.

Second, the emblem indicates that a person works for – or that an object is used by – the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, meaning either a National Society of the Red Cross or Red Crescent, the ICRC or the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). This is called the indicative use of the emblem. The ICRC and the IFRC may use the emblem both for protective and indicative purposes for all their humanitarian activities.

When used for protective purposes, the emblem is large and is just the red cross, red crescent or red crystal, without anything else written next to it. For indicative use, the emblem is small and is accompanied by the name of the user (ICRC/CICR, IFRC, or the name of the National Society).

Any use by somebody not entitled to use it, or for any purposes other than the two mentioned above, is a misuse of the emblem. All states parties to the Geneva Conventions have to prevent such misuses and take measures to address any misuse that occurs.

The strict rules on the use of the emblem are designed to make sure that parties to armed conflict will trust how it is being used and will not attack people or objects using it in line with the rules, or prevent them from doing their medical or other humanitarian work.

Why it is not a good idea to multiply the use of the emblem, or to encourage the creation or display of alternative emblems?

All civilians and civilian objects are protected under IHL by virtue of the fact that they are civilian. Multiplying emblems or extending the use of the existing emblem might be counter-productive, as it may give the wrong impression that a person or object is protected only if it displays an emblem. The protection of civilians and civilian objects under IHL must remain independent from the existence of an emblem.

Medical personnel, facilities and transports are also protected under IHL no matter whether they display the emblem or not. The protection they are entitled to depends on their exclusive medical function. The emblem is just the visible manifestation of protection, it is not what grants them protection. This means that medical units are legally protected, regardless of whether they display an emblem. There is no obligation to display the emblem in all circumstances. In fact, sometimes parties to a conflict have decided not to display the emblem. This is especially the case where they are confronted with an enemy that systematically does not respect medical units displaying the emblem.

In this short clip we tell you all about the rules of war:

Still got questions? Tweet them to @ICRC using #GenevaConventions.