Lebanon: Coping with the disappearance of loved ones

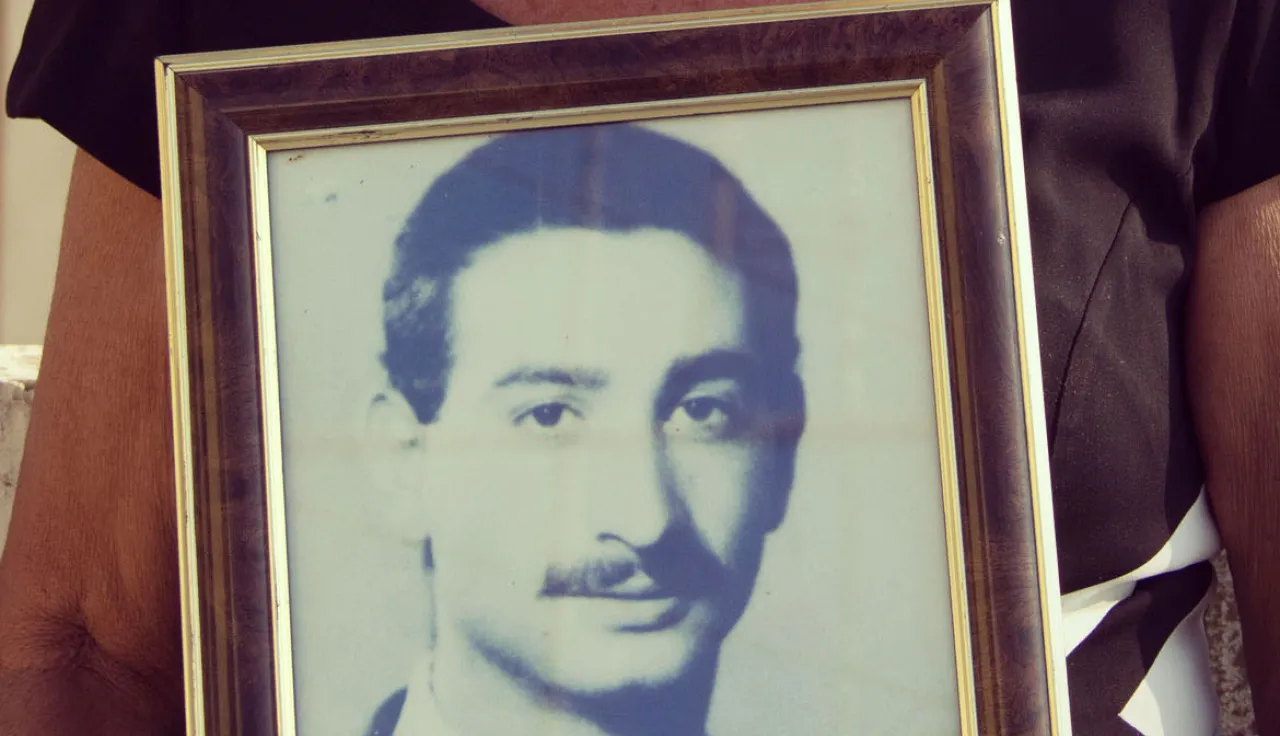

During the 15-year-long Lebanese war that ended in 1990, thousands of people went missing throughout the country. Today their fate is still unknown. For more than 40 years, the families of these missing persons have been waiting for answers, their lives halted and shattered.

In order to help uncover their fate, in 2012 the ICRC launched an Ante Disappearance Data Collection Programme which aims at consolidating a list of missing persons and collecting information that could help give answers to their families once a national commission is formed by the Lebanese government.

During its work, the ICRC noticed that the families of those who went missing had a variety of needs – financial, health and psychosocial among others – that were detailed in a report published in 2013. In order to tend to the psychosocial needs of the families, the ICRC in 2015 launched a programme entitled 'Accompaniment of Missing Persons' Families'.

In an interview for the ICRC in Beirut, Georgios Kanaris, a mental health specialist with the ICRC delegation, explained more about the programme.

Why did the ICRC launch the Accompaniment programme?

In 2011, we conducted an assessment with more than 300 families of missing persons that helped us better understand their needs. Of course, their main concern was the fate of their loved ones. Every single family is still waiting for an answer.

We also noticed that some people were also in need of psychosocial support to help them cope with the disappearance of their loved ones. Many feel guilt and blame themselves, and many cannot sleep peacefully at night. Some still leave space for their missing loved ones at the dinner table every night. There is a lot of suffering.

What is the hardest part when trying to cope with the disappearance of a loved one?

The psychological effect of the disappearance of a loved one is deeply traumatizing. It cannot be compared to any other type of loss. A family whose loved one passes away, for example, can mourn their loss and move forward. The families of the missing, however, see no end to their suffering.

It is almost impossible for families that are unsure of the fate of their loved ones to even consider the possibility that this person is dead. They live in a constant state of hope and despair. This psychological state is defined by renowned researcher Dr Pauline Boss as 'ambiguous loss'. While their loved ones are physically absent, they are always psychologically present and this very ambiguity takes its toll on the lives of the families. Without a concrete answer to the fate of their loved ones, they cannot make sense of their situation to even begin to cope. They are simply stuck.

Tell us more about the programme – how does it work?

The programme aims at helping families cope with the disappearance of their loved ones through psychosocial support groups facilitated by ICRC mental health specialists. These sessions provide the families with a common space where they can share their experiences, thoughts and worries.

It is very hard for the families to find someone who can relate to their pain, so these group sessions help bring comfort to each other and make them feel less isolated. The programme has so far been implemented in Saida district and now also in Baabda district. It also allows the ICRC to further assess the situation of the families and refer them for other kinds of support from local organizations.

What are the future plans for this project?

The first phase of the programme, implemented in Saida district, was very successful. The families really benefited from it and encouraged us to widen it so as to reach more people in need of this type of support.

This led to the launch of the programme, involving 300 families, in Baabda district. From here we intend to move out to more districts around the country to reach as many people as possible. However, it is important to keep in mind that the only way to truly help the families is to uncover the fate of their loved ones and give them answers. This is the only way to end their pain. They have the right to know.