Libya: “There is no buffer for any economic shocks”

In 2019, Libya entered its eighth year of insecurity and protracted conflict. Its economy is in crisis, basic infrastructure is damaged, security threats and severe shortages of cash liquidity have undermined the future prospects of the Libyan population and affected their livelihoods and their access to basic social services.

Faced with the enormous humanitarian needs resulting from the conflict, humanitarian organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) strives to provide response. The ICRC is helping those in need, within Libya, where they live in extremely difficult circumstances because of the conflict. We distribute food and other essential items and support small projects aimed at enabling those affected by conflict who have ideas for projects to achieve economic sufficiency to support their families. In addition to, restoring water supplies and supporting medical services all as part of our partnership with the Libyan Red Crescent.

In this interview with Mohamed Sheikh-Ali, the economic security coordinator from the ICRC’s Libya delegation discusses the current crisis in Libya and the difficulty of providing a neutral and impartial humanitarian response in this context. The deteriorating economic conditions and challenges the population is facing and perspectives about the future.

Can you describe the living conditions and the economic situation in Libya today?

Libya is going through difficult time, a large number of the population is displaced and facing shortage in services. Most of the areas in Libya are experiencing electricity cuts, water shortage, damaged infrastructure, dysfunctional market and banking services. Everything the Libyan population took for granted are not working properly anymore.

The Libyan economy was predominantly estate reliant, 70 per cent of the population were working for the government and 80 per cent of household income was generated through government salaries now most of that evaporated. Today, a large segment of the population is experiencing food insecurity. 64 per cent of the population are now exhorting to negative coping strategies including selling of assets and 75 per cent of household income is spent on food alone and that exposes these families to shocks, so there is no buffer for any economic shocks. This leads to an extreme economic insecurity situation.

Moreover, with the current severe irregularities in payments and the liquidity crisis, over half of households’ struggle to make ends meet. This has in turn reduced the growth of the private sector and the creation of jobs, which further exacerbates the overall economic situation. Female-headed households in particular are additionally affected by the fact that in the traditional and conservative local culture, it is men who are expected to be breadwinners. Thus, female entrepreneurs or those seeking employment are often subject to stigma.

Private sector employment is generally low, and the irregularities of government salary payments leave people without access to cash. The historic reliance on government salaries has hindered the emergence of a culture of entrepreneurship or even the pursuit of alternative livelihoods. No wonder then, the majority of the population report using negative coping mechanisms to be able to pay for healthcare, and up to 80 per cent face challenges obtaining enough money to meet their needs. For example, Al Jufra that has the highest proportion of severely food insecure population (ten per cent), 64 per cent reported to have resorted to negative coping strategies. There are indications that many people in Libya are sliding into destitution. A third of the population in Misrata and Jufra spends more than 75 per cent of their income on food, these households are likely to be more at risk from economic shocks as there is little additional budget available for any other expenses except the most basic requirements. Moreover, 44 per cent of households in Sirte reported using negative coping mechanisms to pay for food, including emergency strategies; the highest rate in Libya. Emergency strategies include selling productive assets, asking for food or money from strangers and accepting degrading or illegal work.

What are the main challenges the population is facing? What about mid/long-term challenges?

“I think the immediate challenge is the conflict and security. However, in the long term the economic challenge and the political instability in the country will be quit overwhelming.”

The overlapping security and economic crisis in the country led to drastic reduction in industrial activities and employment. For example, in and around Tripoli, there were four large juice factories, a milk factory, a soft drinks factory, a pasta factory and a sugar and rice mills. None of these major employers is operating at full capacity now, all of them have reduced workforce.

Disappearing private sector, high cost of living without commensurate rise in salaries, especially the government sector, in which the majority of Libyan are employed had negative impact on the population resilience and the general wellbeing.

Unexpectedly, the Southern Governorates that used to be Libya’s “food basket”, are the most hardly hit by the economic insecurity. The widespread law and order deficiency, aggravated by the hyperinflation of prices made basic needs hardly affordable. The highest prices in the country are found in Southern cities of Brak, Murzuq, Ubari and Ghat, where the food basket cost as much as 49 per cent higher than in rest of the country. This is attributed to the high insecurity, interruption of trade routes and the preoccupation of the two rival governments in enforcing their control in the North. While a major military operation in February 2019 seems to slowly but steadily stabilized the situation, tribal conflicts and fighting caused displacement of entire communities, like some of the Twaregs, from their home towns.

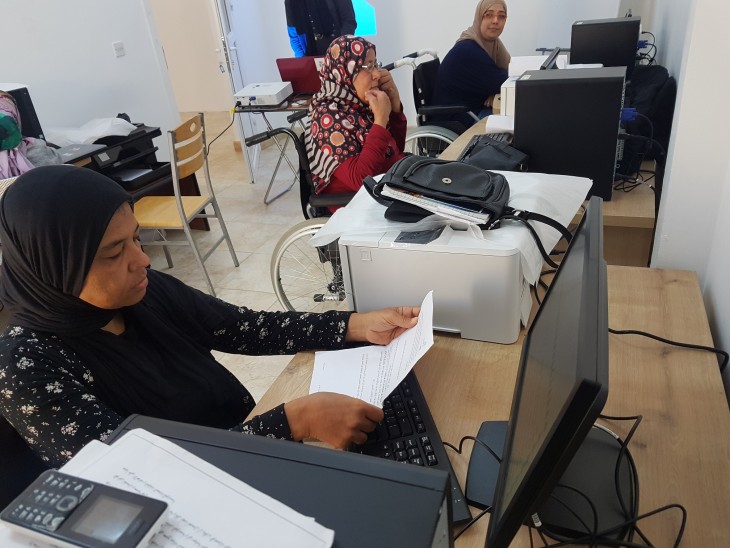

Women with disabilities receiving business plan training as part of MEI program in Benghazi. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Fares Elabeid

Where in the country are the most urgent needs?

The most urgent needs are reported in the areas directly affected by the conflict in Tripoli. However, this shall not mask the many other urgent needs in relatively calmer areas in the country. There are large numbers of vulnerable groups including women raising children on their own, people living with disability, families of the missing, farmers and pastoralist communities in southern valleys.

In Misrata, for example, we have up to 2,000 women who are raising children on their own, at the same level we a large number of people who are living with disabilities.

How has the ICRC’s humanitarian response been like over the year?

As difficult as it is we are trying to address the needs in most parts of the country. There are still areas we don’t have access too but thanks to our partnership with the Libyan Red Crescent who have access to those areas and support in responding to the urgent needs. From relief and remotely delivered assistance to diversified programme aiming at addressing current emergency needs while supporting communities build their resilience through encouraging resumption of independent economic activities.

As much as responding to urgent needs we try to focus on the long-term assistance. MEIs, Agro activities, cash-based assistance etc., helps traders and local market benefit from our assistance and through it we generate market dynamics, improve the market functionality and use the market forces through cash distribution. Local business can benefit from our assistance as well and generate market dynamics When we use cash aid, we do not only look at the immediate need of the family that we are assisting, but we aim as well at encouraging the economic activities in the area.

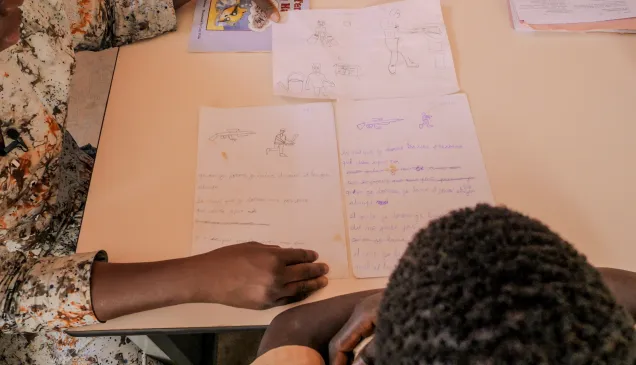

For example, widows and disabled persons are receiving micro economic initiatives grants so that they can start a small business. We, as ICRC, train them so that they can start delivering services independently.

So, our programme is designed in a way we address immediate needs but at the same time help communities to recover and to resume their regular activities.

Women receiving tailoring training as part of MEI program in Misrata. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Mohamed Abdulhakim Lagha

Are there any stories you can share of people that have been most impacted by this crisis?

In Benghazi, we are supporting a group of disabled women’s who have started an association where they produce confectional products they sell to generate income. At the same time the facilities and the services we provided are being used to train and coach these women’s who are often marginalized and quit often suffering from psychological issues. Being at a position of lead these women’s now feel that they can be part of the society and contribute to a meaningful cause. As much as we believe in the humanitarian cause and it’s nobility this is exactly what encourages us and keeps us moving and expanding.

What’s your perspective about the future?

“Unfortunately, the future is not promising, and I hope the conflict will end soon.” That economic deterioration, if it’s not addressed, will lead to a slide into destitution for a large part of the population.

What gives you hope?

“Things that gives me hope is the commitment of the people we are working with.” When I see young men who in the past used to receive salaries from the state coming and requesting vocational training and ready to work, that itself gives me hope. Some of the commitment of local authorities who are despite the conflict trying to stay away from the politics and deliver the services for the people and maintain the decaying infrastructure, water, health, markets, that also gives me hope.

At the end, I hope those grassroot initiatives will get the support they need and deserve.”