Speech given by ICRC President at National University of Mongolia

Speech given Peter Maurer, President of the International Committee of the Red Cross, on the transformation of conflict dynamics and their humanitarian consequences at the National University of Mongolia.

Mr. President, (Mr. Bat-Erdene)

Ladies and gentlemen,

I am grateful for the opportunity to address you today at the National University of Mongolia, which educates and trains the country's leaders of tomorrow. This institution is leading impressive efforts of international outreach, and I hope one day soon to be able to count some of its graduates among the International Committee of the Red Cross' 15,000 staff worldwide.

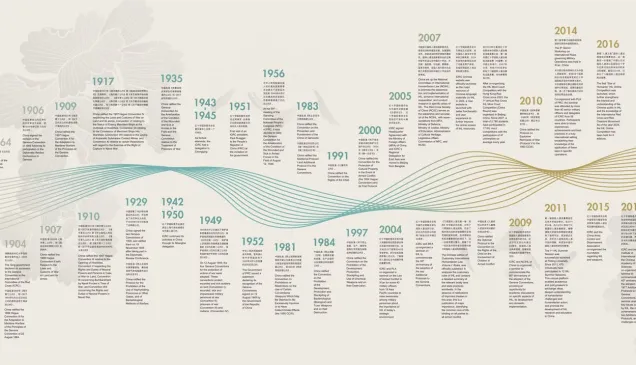

The ICRC was founded, over 150 years ago, as a neutral, independent and impartial humanitarian organization, committed to assist those in need and protect the lives and dignity of victims of armed conflict and other situations of violence.

Today, I would like to give you a brief overview of how the ICRC looks at the global transformation of war and violence. Also, I would like to illustrate, how we are trying to access people in need, to protect them from the impact of conflict and violence, to deliver essential aid and to create a space for neutral, impartial and independent humanitarian action.

Across the world, the number of wars is decreasing. That should be good news. But in reality only the number of all-out international armed conflicts are decreasing. Internal armed conflict and long-term, protracted situations of violence are increasing. We see a new type of conflict and violence emerging, with new dynamics that create new challenges for humanitarian responders:

- Protracted conflicts that are ever longer in duration and affect basic social delivery systems like water distribution, health, shelter or education – for example in Afghanistan, Somalia, the DRC or in the occupied Palestinian Territory.

- Regionalized conflicts, which spill over into neighboring countries – like the violence in northern Nigeria that is affecting Niger, Chad, Cameroon and other countries; the Syrian conflict, which has destabilized the entire Middle East or the Somali and Sudanese conflicts, which affect the Horn of Africa as a whole.

- Volatile conflicts spiked with terror tactics and spread through the ideological battleground of social media – for instance in Iraq, with deadly suicide attacks as a particular challenge.

- Politicized and increasingly polarized conflicts with few perspectives for political settlement that we see unfolding in Ukraine or Yemen.

- Battlefields that extend into cities and civilian's communities, with bombing and attacks in densely populated areas, affecting cities like Aleppo, Homs, Mosul, Tripoli, Bengasi, Luhansk, Donetsk or Gaza.

- Violence imposed by new actors, which mix political, criminal and business interests in amorphous structures, for example in Central America.

- Conflicts that unfold increasingly in middle-income countries, where the link between poverty and conflict is less present and the humanitarian response needs greater sophistication.

As regards international relations, power shifts and power competition at global and regional level are visible on each and every corner. Unfulfilled expectations and empty promises of development, peace and justice in the implementation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), combined with faster communication and increased awareness of States' and the international community's failures, have created an environment of tensions within societies and between States. Tensions have arisen, in the Arab world in particular but not only, between rigid political systems, aspirations of people and deep injustices in societies.

The ICRC is, logically, confronted with challenges due to the recent transformation of warfare:

- Asymmetric conflicts involving state and non-state armed groups and their respective differences

- The fragmentation of actors

- Moving and dissolving borders

- The globalization of battlefields

- Warfare based on terror tactics

- The scale and spread of secret and remote warfare including special operations

- The State-like posturing of some non-State actors, and the list goes on.

The ICRC has been particularly challenged because some of the fundamental assumptions of the Geneva Conventions are being questioned through these new developments:

The Conventions are based on a careful balance between military necessity and protection of civilians. According to this logic, armed violence is accepted, when linked to a "military advantage" and under the condition that restriction with regard to the conduct of hostilities are respected (distinction, proportionality, precaution). Such military advantage is much more difficult to assess, if the battlefield is global and war has no timeframe.

Because we work on and across frontlines, based on dialogue with all weapons bearers ready to engage, we are particularly exposed to these developments, and the operational access and safety of my staff depends on our accurate reading of such evolutions. The situation in which we find ourselves, has led us to undertake much more comprehensive security analyses in order to support our field missions and invest in much more complex and systematic negotiations in order to have assurances from all parties to the conflict, who give us our "license to operate".

This new environment may render our work in favor of respecting international humanitarian law more complex, but it also makes it more necessary.

A more layered environment correspondingly leads to broader humanitarian impact, with

- Sky-rocketing internal displacement and refugee numbers – 60 Million people displaced by violence of which 45 millions are internally displaced and "only" 15 million refugees, while an additional 10 Million people are stateless.

- With regional pressures on social delivery systems leading to system failures: housing, nutrition, water, health, education are interdependent systems, which collapse when the cumulative impact of urban warfare or protracted conflicts hits.

- With important indicators showing disturbing trends like the pace at which communicable and non-communicable diseases are growing and outpacing the growth of those dying from violence; the days children spend out of school is outnumbering the days children are at school: the indirect causes of conflict are then more serious than the direct consequences.

The deepening impact of violence on people also leads to skyrocketing costs: the cumulative international humanitarian response has surpassed 25 billion US dollars annually, delivered by more than 200'000 people, to respond to 125 million people in need. At the same time the cost of global conflict is estimated at around 10-15 billion US dollars per year.

As humanitarians we have to simultaneously increase assistance activities, engage more forcefully on our protection mandate and raise more funds, through new innovative partnerships and products, with an eye on the fragile environments, where escalations can rapidly lead to exploding humanitarian needs. As the guardian of the Geneva Conventions, we have to engage with a growing number of arms bearers, in order to change their behavior to create a less damaging impact for the civilian population.

Even more importantly, we must ensure greater respect for international humanitarian law (IHL) and the humanitarian principles of neutrality, independence and impartiality.

For the past 150 years, the Geneva Conventions and other bodies of international law have codified the limits of war. These limits of war are not only to be found in international humanitarian law; they are universal human norms, which have existed for thousands of years, based on the intrinsic value of humanity, dignity, protection of the vulnerable and service to those in need.

Yet there is a range of issues that considerably complicate respect for the law. Let me enumerate some of them which the ICRC is currently working on.

A first issue is one of compliance with the existing treaty and customary rules of IHL, something that is at the core of the ICRC's activities related to the protection of persons in armed conflicts. The ICRC works to improve compliance with IHL, by being present on the ground and by maintaining a bilateral confidential dialogue with State and non-State actors to address specific humanitarian problems.

In parallel, the ICRC also works to enhance compliance with IHL through activities designed at fostering understanding and acceptance of IHL, as well as assisting authorities in the implementation of IHL in domestic law. Such efforts also include reaching out to influential circles, including religious and community leaders and scholars, which enable us to better understand how value systems relate to the law of war, and to identify commonalities with IHL. This may be especially relevant, when certain non-State armed groups reject IHL as a whole in the wrong conviction that it is a Western creation.

But we have to recognize that compliance with IHL is heavily dependent on the political will of the parties to a conflict. The Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I provide for a whole series of mechanisms to strengthen compliance, but they have rarely, if ever been used. The reason for their failure is that their functioning is subject to the consent of the parties concerned. They were designed for international armed conflicts, not non-international ones. Similar challenges overshadow mechanisms established under the UN. They too are subject to political negotiation and selective in their choice of which situations to address.

Another issue complicating respect for the law is related to the deprivation of liberty of persons. In international armed conflicts, IHL clearly states when and why a person can be detained or interned. Things get more complicated in situations of non-international armed conflicts, where IHL is far less precise.

The reason for this lack of certainty and lack of clarity is that IHL applicable in non-international armed conflict assumes that internment will occur, but it fails to clarify the permissible grounds and required procedural safeguards, which leaves detaining authorities without pre-determined rules under IHL to rely on against arbitrary detention. In this situation IHRL is an important guide. The problem as such is a recurring issue in legal studies: the world and societies evolve faster than the law and we find ourselves with a legal gap or ambiguities.

Moreover, international humanitarian law and human rights law partially overlap, yet partially leave a gap, most frequently where the clarity of the law is met with a much more complex, multi-layered reality on the ground.

Likewise, issues such as the transfer of a detainee from one State to another, material conditions of detention, including food, shelter and medical care, contact with the outside world, or specific needs of women and children or of particularly vulnerable persons such as the elderly or disabled, are not sufficiently regulated in non-international armed conflicts.

The ICRC works, together with States, to address these issues, and find both practical and legal solutions to the existing gaps.

While the main challenge for improving the situation of victims of armed conflicts is ensuring respect for existing norms, one cannot ignore the evolving ways that wars are fought in the 21st century. The rapid evolution of military capabilities is a case in point.

The Geneva Conventions give the ICRC a mandate to work on the humanitarian impact of weapons, always following the rule that all warfare must respect the principles of precaution, proportionality and distinction. We see it as a success that we managed, together with States, to enforce a ban on anti-personnel mines, and massively regulate the trade of small weapons through the Arms Trade Treaty.

However, to make these successes last, support by all States is essential. I would like to use this opportunity to encourage Mongolia to continue in its process of committing to both of these legal instruments, by formally ratifying the Arms Trade Treaty, and progressing in its accession to the Mine Ban Treaty, as foreseen.

We are currently working on the issue of explosives in densely populated areas. While the battlefield has moved into cities, we cannot accept that the weapons move along into urban centers, too close to family homes, hospitals and schools.

New methods and means of warfare – such as cyber warfare and autonomous weapons - have become subject of increasing debate in the humanitarian, legal and diplomatic community. Clearly, the drafters of the Geneva Conventions did not foresee such technologies. Such new weapons raise issues of keeping principles of distinction, proportionality and precaution up when the cyberspace is interconnected; it also raises issues with regard to the identification of attackers, who may remain anonymous; it raises some fundamental questions with regard to autonomous weapons about how machines can be allowed to make life and-death decisions or about who would be held accountable for war crimes.

Let me be clear, the crucial question is not whether new technologies are good or bad in themselves, but to make sure that they are not developed and employed prematurely under conditions in which respect for IHL cannot be guaranteed.

In this context let me also mention

- The increasing difficulties in today's contexts of conflict to distinguish between combatants and civilians, in particular those civilians who temporarily participate in hostilities.

- The increasing juxtaposition of military assets with civilian infrastructure;

- The lack of clear applicability of the rules, which allow parties to escape their obligations by arguing that the law does not apply to counter terrorism operations;

- And overall, the sense that the law does not provide a satisfactory framework to prevent or prohibit the increasing violence and ensure accountability of perpetrators.

All these factors contribute to a certain level of insecurity.

At the ICRC we base our actions on the limits of war – not because the Geneva Conventions allow us to do so, but because where the limits of war are not respected, men, women and children who have not taken up arms – or combatants who have laid down their arms – are deprived of protection from murder, rape, pillage, humiliation, and the list goes on. We base our actions on the needs of people affected by conflict and violence, wherever this leads to humanitarian consequences.

Because of the lack of compliance and the insecurities on how to adequate the legal framework with complex conflict realities of today, it has become fashionable in certain circles to consider IHL outdated or eroding to insignificance. While problems cannot be neglected, one has to recognize that

- IHL helps save lives each and every day in settings of conflict and violence

- The very existence of the legal framework provides a common basis and a vital role in our continuous dialogue with parties to the conflict

- It is at the origin of so many weapons' treaties, which have contributed to mitigate and limit suffering

- And it reflects the right thing to do morally.

The positive impact of the law is too often hidden under the broadly publicized violations of IHL, creating thus an image of a law that is failing.

Our experience shows that neutral, independent and impartial humanitarian action based on International Law has the best chance to reach those most in need. It is also a tried and tested formula to prevent that humanitarian action is becoming part of larger and more controversial political agenda.

Yet the humanitarian space necessary for our work is becoming increasingly difficult to navigate against the new type of conflict and actors that are dominating today.

In Latin America for example, a continent not unfamiliar with armed violence, the last two decades have seen the emergence of new forms of armed violence that are generating alarming levels of humanitarian consequences for the populations of many, if not most of the countries of the continent. In Brazil for instance, as many people died of homicides last year, as people were killed in the war in Syria during the same timespan.

Much of the violence today no longer stems predominantly from political confrontations, but seems to be driven more and more by motives related to other gains, including through illegal activities such as drug trafficking. Despite such trends, the humanitarian consequences identified are often similar to those experienced in contexts of more traditional patterns of violence such as armed conflicts or in internal disturbances. Such consequences include people being killed, wounded or going missing. But there are also consequences directly generated by general insecurity:

- For example when people are prevented from accessing basic services such as healthcare and schooling because it is dangerous to go out in the street,

- Or when they feel compelled to move from their homes to other places either within their country or abroad due to the lack of social or economic opportunities or for fear that something might happen to them or their families.

It is obvious that such a scenario poses a series of challenges for authorities and humanitarian actors alike. The perpetrators of such violence are not always accessible nor possible to control and are not necessarily concerned about the well-being of the population. In the same way, communities or individuals who live under constant fear of the threat of violence are not always forthcoming in reporting problems - much less so those who find themselves in another country without the correct documentation. Even when a clear desire to improve the situation is expressed, the resources available are not always enough, leaving gaps in services or procedures designed to protect the most vulnerable and exposed.

Unlike other organisations, the ICRC does not focus only on one specific area like health or food. Also we do not focus on a specific group like children or women, nor on one specific type of activity like assistance or advocacy. We are committed to responding to an extensive variety of needs (food, water and sanitation, health, basic household items) and describe ourselves as a multidisciplinary organization. We focus on the most urgent needs of people and thus on a broad range of vulnerabilities - we are radically needs-based in our approach and work in direct proximity of victims. We are not just a relief agency but committed to assist and protect and to influence weapon bearers so that they respect the law and thus the limitation of the use of weapons. Finally, we try to influence actors on the ground to better protect civilians.

With such an approach, our response is distinct and different throughout countries and regions. We have a very different exposure today in the Middle East, in Africa, here in Asia or in Latin America.

Often, I am asked which one the worst of all conflicts is, in which we operate, the most difficult crisis, with which we deal. The answer to this question depends on criteria:

- If we look at long term, protracted conflicts, Yemen, Israel/ Palestine, the DRC or Afghanistan come to mind.

- If we look at numbers of people living on the edge of survival, because poverty and violence has thoroughly destroyed social fabrics, the CAR, the Sahel, South Sudan or Somalia come to mind.

- If we look at the spiral of violence, destruction and displacements, Syria and Iraq are amongst the most difficult situations.

What strikes me today is that humanitarians have to adapt to a series of different realities: humanitarian assistance and protection in poor and middle-income countries, with more or less local capacities, with more or less funcitoning markets, providing supplies to populations, with needs in rural and urban areas. Responding to such multi-faceted problems is a big challenge to humanitarian actors and systems.

The first World Humanitarian Summit, which will take place in Istanbul this May will be an opportunity not only to remind States of their foremost responsibility to respect IHL and ensure respect for it; but also address some of the big challenges of today - linking international and national/local efforts, in bringing private and public contributions closer to respond to needs, in calibrating humanitarian action short and long-term, in addressing mass displacements, violent extremism, health system reforms or the financing of humanitarian actors in the future. The ICRC, part of the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement maintains that its distinctiveness as a neutral, independent and impartial actor is key to its achievements.

Indiscriminate violence in the form of terrorist attacks around the world – the latest tragic events in Lahore, Brussels, or Istanbul come to mind – has created a widespread feeling of insecurity and led to increasingly robust State responses. It is important to note in this context that all intentional attacks against non-combatants and all attacks aimed at spreading terror are prohibited under International Humanitarian Law.

The ICRC will continue to loudly remind all parties of the need to preserve humanity and to apply international humanitarian law (IHL) and other relevant frameworks, such as human rights law, as a means of preventing and dealing with such unacceptable acts of violence. We are redoubling our efforts to ensure that the law is known, understood and respected and to underline that the use of force must be within the boundaries of the law; that the treatment of detainees according to international standards has a clear role to play in the quest to reduce acts of terrorism and other forms of extreme violence.

Our engagement worldwide with those who carry the weapons, and our experience in visiting hundreds of thousands of detainees every year, place us in a strong position to guide governments on how best to abide by the rules of war. Nevertheless, States must uphold the standards of humanity when making the difficult choices surrounding military and security action.

Meanwhile, not least due to protracted conflicts and chronic poverty and violence, global migration has reached unprecedented dimensions, with more people displaced than at any time since the Second World War. We have to remember that nobody leaves their home, their family, their entire life behind, on a whim. People flee for a reason, and these reasons will not disappear anytime soon. This crisis is far from over.

While politicians continue to discuss their individual response to migration, the humanitarian position is much clearer: the first driver for humanitarian assistance and protection for migrants must be their vulnerability, while their legal status determines their rights. Vulnerabilities and rights must not be pitted against each other. And: States cannot focus on what happens inside their borders alone. Migration routes go across borders, and so must our joint response.

Sticking migrants in camps is not a solution. We must give them the capacity and opportunity to lead normal lives. States must therefore make resources available in line with the existing, dramatic needs.

The ICRC, as part of the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement, will continue to provide health and other material assistance to vulnerable migrants, to reach out to their families where possible, and to support those detained, particularly minors. We will continue to support communities in the countries of origin and neighboring regions, close to the front lines of the conflicts which are the sources of first displacement, so that fewer people will be forced to flee their homes.

We do so in Europe, in Latin America, but also on the Asian continent. Afghanistan constitutes one of our biggest operations worldwide, and I know that Mongolia is following the developments in Afghanistan closely, with a presence inside the country.

We have seen rising numbers of war victims, displaced, disabled, and besieged civilians there in the last years. Our first concern is how to deliver and increase humanitarian assistance amid violence and conflict. Access and security negotiations, the two indispensable elements to successful humanitarian action, are complex by nature, but become even more volatile when ongoing fighting can jeopardize agreements and assurances.

The Afghan conflict, which used to be more clearly characterized by two main parties – the government and the Taliban – is increasingly seeing a multiplication on the non-State actor side, with diverse groups including the Islamic State Group leading to a broadening of the conflict in terms of actors and territory, including to formerly comparatively quiet parts of the country.

Of course, Mongolia itself is also committed with troops in Afghanistan, besides Mongolian peace keepers active in the UN missions in South Sudan and Darfur.

I know that the projects for Mongolia to commit to "permanent neutrality" are underway, and in a critical stage at this time. Coming from a neutral country myself, Switzerland, I can tell you that neutral facilitators are appreciated, and have a crucial role, in all conflicts.

The Ulan Bator Dialogue on Northeast Asian Security will hopefully become a marked example of this. In the tense environment of the Korean peninsula, a reliable partner that is trusted by all parties can sometimes open the window of opportunity needed to bring about change, including access for neutral, impartial and independent humanitarian actors.

The same can be said for many other contexts. In Ukraine for example – the ICRC's 8th largest operation in 2016 – we are currently the only international humanitarian organization present and active on all sides of the conflict. And the ICRC continues to this day to be the only international humanitarian organization working in Crimea.

I must say that the ICRC is confronted with great complexities concerning the dialogue on the conduct of hostilities in Ukraine, as well as access to certain places of detention. Our capacities currently go beyond our opportunities and we will continue to work towards greater balance, in line with our mandate and aim to protect civilian populations. The politicization and instrumentalization of humanitarian action, by any party, can in this regard be severely damaging.

On the other hand, the ICRC benefits from trusting relationships. When States among themselves share their respective experiences of ICRC action in their countries, this helps us build trust, and thereby expand our operations to help more people.

In Myanmar, for instance, the ICRC has been present for 30 years, visiting detainees, improving health care access, providing physical rehabilitation services and supporting communities in need. A large part of our work around the world is engaging States and authorities regarding international humanitarian law. The support of a neutral friend is welcome when it can lead to greater respect for the law.

Beyond our work on legal frameworks, and our operations on the ground, we engage in advocacy, too. Creating awareness and spreading information about some lesser-known sides of the humanitarian consequences of armed conflicts, can help prevent suffering.

Sexual violence for example – against women, men, boys, girls, and detainees – has been part of wars for centuries, all over the world. But it is a war crime. We aim to educate and inform military, other weapons carriers and communities about the risks, the suffering and the essential medical and psycho-social treatment for victims of sexual violence.

On a daily basis, we see a widespread failure to respect IHL, and we see a failure to ensure respect for IHL, as is the duty of all States and non-State actors, according to the Geneva Conventions.

These rules are too often ignored and violated, while they are the only thing that can protect people during war. We must be honest with ourselves: collectively, we are failing to protect the most vulnerable from the impact of armed conflict and violence.

A striking example of this failure is the frequency of attacks on health-care facilities and personnel, globally, despite their specific protection under IHL. We need a renewed commitment to respect the law, the spirit of the law and its intent: maximum precautions in attack and zero tolerance for mistakes.

Two years ago, we launched a campaign on the matter of protecting healthcare facilities and staff. Because what happens when hospitals are attacked, or doctors and nurses targeted? When medical aid is blocked from delivery? People suffer longer and more. A few months ago, in Yemen, a plane carrying medical equipment was prevented from landing. This meant that hospitals could not treat patients. And wounded people were quickly filling up the hospital, but the medicine still hadn't arrived. The same week, a colleague of mine was shot while driving an ICRC truck to get more medicine for a hospital in northern Mali. The security of our staff has to be a priority – so how can we work when we are being attacked for doing our work?

At the ICRC we believe in making every effort to marry practical experience, policy and law. This way, we can counter the fatal spiral of violence and disrespect for the law with strong encouragement for practical humanitarianism, supported by strong law and decisive political action.

Thank you.