Ukraine crisis: Snapshots of despair in Sviatogorsk

Conflict in eastern Ukraine has claimed more than 5,000 lives and destroyed many more. According to UN figures, the confrontation has now displaced more than a million people. The town of Debaltsevo, upon which some of the fiercest fighting has centered in recent weeks, has seen much of its population evaporate into the freezing winter. Many have scattered to surrounding towns and villages such as Sviatogorsk, some 100 kilometres to the north-west.

Against the backdrop of the ceasefire agreed in Minsk on 12 February 2014, the ICRC is working on both sides of the front line to bring aid to those who have fled their homes. Dmytryo Marchenko is a humanitarian worker based at the ICRC's Kharkiv office. He sent this report after a field visit to Sviatogorsk, where he and his team recently distributed essential aid to displaced people.

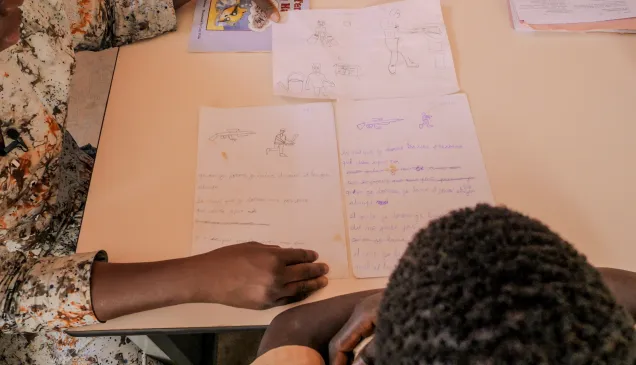

6 February 2015, 9 a.m. It is still dark, but in spite of the icy wind and heavy snow, a small crowd has gathered in front of the warehouse located in what was once Sviatogorsk's leisure district, where tourists used to flock to visit the popular sanatoriums of the fashionable spa town. Today we are distributing food and hygiene items to people who have recently been forced to leave their homes. Since fighting flared again in early January, several thousand civilians have fled what has become known as the "Debaltsevo pocket" because of the way the front line snakes around it.

A group of volunteers from a local NGO are helping our small team. All of them are themselves displaced, but they have been in Sviatogorsk since last summer and are keen to help the new arrivals. Gusts send snow swirling around the people who stand waiting, bundled up in their coats and scarves. The cold is intense but no-one is willing to leave without checking if they are eligible for aid – 60 kilos of food and a box of hygiene items per household.

Quickly, we set up our registration desk. Displaced people organize themselves into a queue, silently. As they come forward to register one by one at the desk, I chat with them. All of them look weary and cold, and all have large, dark shadows under their eyes.

ICRC warehouse, Sviatogorsk, Ukraine. Displaced people collect food and hygiene supplies.

CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / D. Marchenko

An old woman sways out of the queue and sits down on a stone covered in snow. "I've been standing for five days already and my legs can't carry me anymore," she says. "I had to stand in the bus that got us out of Debaltsevo, then I had to walk for a day and a half to find a room in Sviatogorsk, then I had to queue to register with the City Council as an internally displaced person. I queued for a whole day but I didn't get to the desk, the queue was too long. I had to come back the next day and queue again. I was registered yesterday some time after 3 p.m. That was the second day that I'd had to stand since early morning without nothing to eat. Now I'm tired and very cold, and I don't have the strength to queue any more." Around her, people nod. "Same for me," a woman says, "and we had to bring our children with us too!"

The woman who just spoke is accompanied by a girl of about 9 or 10. The child holds on firmly to the pocket of her mother's coat with one hand. With the other, clenched into a hard little fist, she rhythmically hits herself in the mouth. "Are you entitled to special assistance for your daughter?" I ask gently. The mother immediately understands my real question. "No," she replies bitterly, "my daughter does not have a learning disability. She's just spent three weeks in an underground shelter in Debaltsevo while bombs were destroying our neighbourhood."

A younger woman joins in the conversation. She has a baby in her arms and a fresh wound on one hand. "I was in an underground shelter in Debaltsevo too," she says. "But my baby was crying all the time because of the shelling and the darkness, and the others couldn't take his screaming any longer. It was very embarrassing. In any case, there was no light in the shelter, and I couldn't feed my child or keep him clean, so I decided to go back to my flat. Five days ago, I went out into the street to look for water. There was an explosion and something hit my hand. I don't know what it was, but when I saw the blood I knew that it was time for me to go."

People start to chat. The main topic is family and friends who have stayed behind. Several of them, women in most cases, insist on giving us the names and addresses of relatives who have remained. "Please don't forget them," they say. "They have nothing and they want to be evacuated, please help them." "They need medicine, food, blankets..." "They're collecting dirty snow in the street to melt and drink, they have no water." "Whatever you can give them will be a blessing."

The distribution suddenly grinds to a halt. One of the volunteers helping us for the day has just received a call from a neighbour. The volunteer fled Donetsk at the end of last summer when her house was damaged by a rocket. It has been hit once again, and the fire brigade were unable to reach it due to the shelling. Her house has burnt down to the ground.

I find her sobbing behind the stack of hygiene parcels. I try to comfort her but months of living with exile and precariousness are catching up with her and she cries, hard, for several minutes. "I may no longer have a past, nor any place to go back to, but I can still help others and that is what I am going to do." Bravely, handkerchief in hand, she goes back to the registration desk.