Why autonomous weapon systems matter in Africa

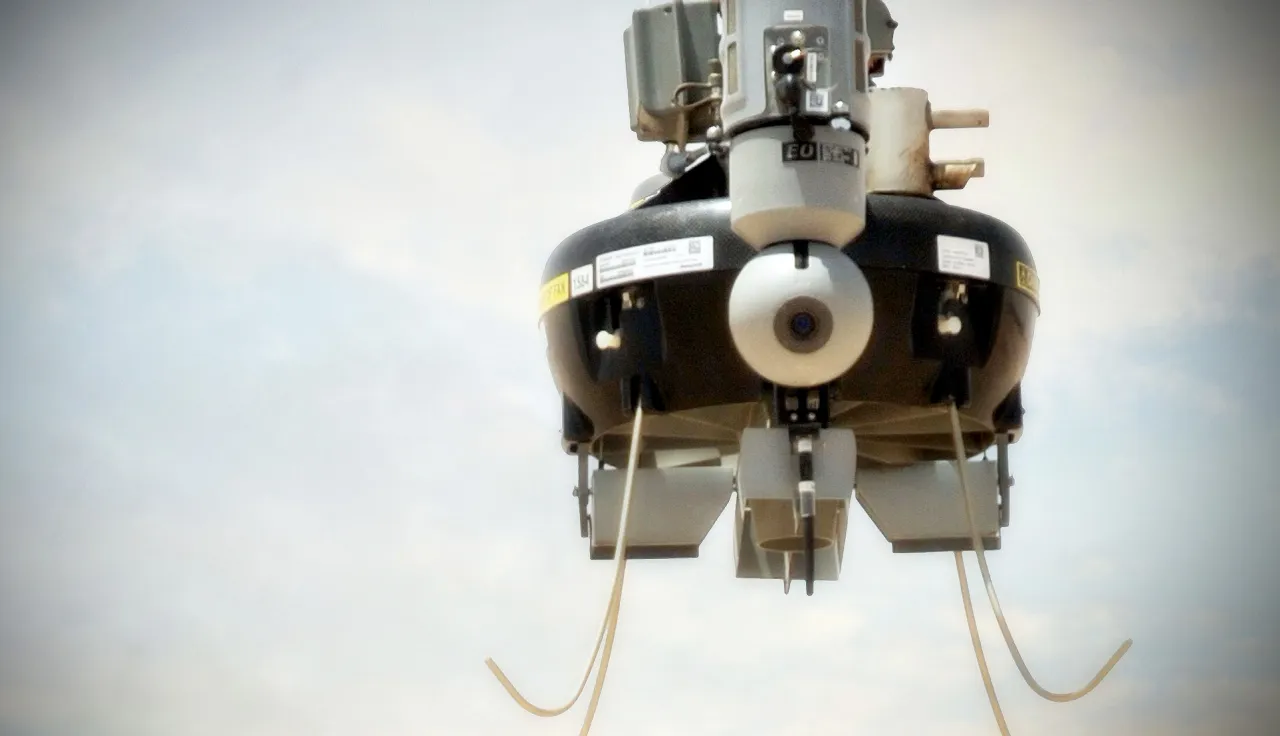

T-Hawk remotely piloted air system in Afghanistan. © U.S Army

As rapid advances continue to be made in new and emerging technologies of warfare, notably those relying on information technology and robotics, it is important to ensure informed discussions of the many and often complex challenges raised by these new developments. One emerging category of weapon of particular concern is autonomous weapon systems.

These are weapons that can, once activated, select and attack targets without human intervention. And their development raises legal, ethical and societal questions.

Following a recent ICRC experts meeting entitled "Autonomous weapon systems: Implications of increasing autonomy in the critical functions of weapons", held on 15 to 16 March 2016 in Switzerland, we spoke to ICRC legal adviser Gilles Giacca to assist us in navigating the key issues

What are the characteristics of autonomous weapon systems?

There is no internationally agreed definition of an autonomous weapon systems but common to various proposed definitions is the notion of a weapon system that can independently select and attack targets. The ICRC has proposed that an autonomous weapon system is one that has autonomy in its 'critical functions', meaning a weapon that can select (i.e. search for or detect, identify, track, select) and attack (i.e. use force against, neutralize, damage or destroy) targets without human intervention. This definition is broad and encompasses some existing weapons such as missile and rocket defence weapons; vehicle "active protection" weapons; anti-personnel "sentry" weapons; sensor fused munitions, missiles and loitering munitions; and torpedoes and encapsulated torpedo mines.

Are autonomous weapons systems able to comply with the fundamental principles of International Humanitarian Law, in particular the principles of distinction and proportionality?

While the primary subjects of IHL are States, IHL rules on the conduct of hostilities (notably the rules of distinction, proportionality and precautions in attack) are addressed to those who plan and decide upon an attack – not to a machine. These rules create obligations for human combatants and fighters, who are responsible for respecting them, and will be held accountable for violations.

Therefore, compliance is achieved by the manner in which a weapon system is employed by a human in a particular situation. Based on current and foreseeable technology, ensuring that autonomous weapon systems can be used in compliance with IHL could pose a formidable challenge if these weapons were to be used for more complex tasks or deployed in more dynamic environments than has been the case until now.

Who would be held responsible for decisions being made by autonomous weapon systems? Is there an 'accountability gap' in the event of an IHL violation?

It should be clearly emphasized that States are responsible for ensuring that their armed forces are capable of conducting hostilities in accordance with its international obligations. So this is rather straightforward – a State could be held liable for violations of IHL caused by the use of any autonomous weapon systems under general international law governing the responsibility of States for internationally wrongful acts.

As for the criminal liability, the use of increasingly autonomous systems would not change the fact that a commander, an operator, or other individuals involved in the operation remain liable when using an autonomous weapon systems. If the weapons are used in an unlawful manner, for example deploying in a populated area an anti-personnel autonomous weapon system that is incapable of distinguishing civilians from combatants, then the commander who ordered the deployment would be held criminally responsible.

As long as there will be a human involved in the decision to deploy the weapon to whom responsibility could be attributed, there might not be an accountability gap.

A robot armed with a futuristic weapons system at an exhibition in Tokyo. ©Reuters/K. Kyun Hoon

What is the role of weapons review procedures in this debate?

In accordance with Article 36 of Additional Protocol I, each State Party is required to determine whether the employment of a new weapon, means or method of warfare that it studies, develops, acquires or adopts would, in some or all circumstances, be prohibited by international law. Legal reviews of new weapons, including new technologies of warfare, are a critical measure for States to ensure respect for IHL.

It should be mentioned that weapons review is not only a purely legal question, but it may entail ethical and policy considerations. However, one has to keep in mind that, despite this legal requirement and the large number of States that develop or acquire new weapon systems every year, only a small number of States are known to have procedures in place to carry out legal reviews of new weapons.

Further efforts are needed to encourage States to develop a formal procedure. The ICRC has suggested that these efforts to encourage implementation of national legal reviews are not a substitute for States party to the UN Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) to consider possible policy and other options at the international level to address the legal and ethical limits to autonomy in weapon systems. Rather these two approaches are very much complimentary.

Following the recent ICRC experts meeting on autonomous weapon systems, could you share with us insights which came out of the meeting in relation to the limits of autonomy?

The debate is moving forward. This second expert meeting organized by the ICRC brought together 70 government and independent experts, including representatives from 20 States, including Egypt and South Africa. The meeting contributed to a better understanding of the technical characteristics of autonomous weapon systems, which provides insights on the current status of weapons development.

A number of challenges remain concerning the scope and aim of the discussion. The definition of autonomous weapon systems remains a point of divergence among States. While some distinguish between the terms "automated" and "autonomous", others regarded these terms as interchangeable. The question of "predictability" of autonomous weapons systems was mentioned as a key factor for complying with IHL, but also as an important factor of military utility. ¨

The framework of human control was also broadly discussed. It can provide a useful baseline and collective language from which common understandings can be developed among States, and through which boundaries or limits on autonomy in weapon systems can be established. This is because most stakeholders believed that the need to maintain human control over weapon systems and the use of force is consistent with legal obligations, military operational requirements, and ethical considerations.

Autonomous weapons are often perceived as far removed from the issues facing Africa. Do you think African states, civil society and other concerned stakeholders should be involved in the debate?

African States, like any State, should be involved in the legal and policy debate on new technologies of warfare. South Africa, for instance, is an arms producing country that has developed highly automated active protection weapon systems for tanks.

Debates on autonomous weapon systems have expanded significantly in recent years in diplomatic, military, scientific, academic and public forums. These have included, among others, expert discussions in the frame of the CCW in 2014 and 2015, which will continue from 11-15 April 2016.

This is another reason why all African States should join the CCW and its Protocols because they have an important role to play to shape the debate. A number of African countries have been active in the CCW context such as South Africa, Sierra Leone, Egypt, or Mali, all stating that the use of autonomous weapon systems must comply with fundamental principles of IHL.