Hugo Slim: ICRC partnerships, today and tomorrow, in conflict and disaster

The ICRC head of policy, Dr Hugo Slim, gave a speech at the 5th Singapore Red Cross Humanitarian Conference on the theme of partnerships and volunteerism for humanity on 20 July 2019.

It is a very special year for the Singapore Red Cross because it is your 70th anniversary year and you have so much to be proud of over the last 70 years – so many humanitarian achievements.

Today – at 70 years young – you continue to be an impressive organization that is highly focused and effective within Singapore and a very active National Society internationally around the world.

And, you are a twin! You share your 70th birthday with the Geneva Conventions. Both born in 1949, you two twins stand for the same universal value – the principle of humanity, which asks us all to "protect and alleviate human suffering wherever it may be found and to protect life and health and ensure respect for the human being." And we are asked to do this in the best of times and the worst of times.

With the magical age of 70 comes great wisdom.

And one of the things that every wise humanitarian will tell you is that humanitarian work is best done together. It is never a solo performance. It always relies on mutual support of various kinds.

Humanitarian action is best done in partnerships - by working with others – which is why this year's conference theme is such a good one. The ICRC is very old, and, like the Singapore Red Cross, we too are reminding ourselves of the important truth of partnership this year. Our new institutional strategy has partnership as one of our five major strategic objectives as "working with others to enhance impact". We are doing this for three main reasons:

- The long-lasting conflicts of today and tomorrow mean we need the help and support of others to have a bigger and more sustained impact in the lives of people who are struggling to survive conflict and violence, often for decades and through multiple generations.

- The escalating climate crisis will mean a large expansion of human needs in the years ahead and make humanitarian action more even more complicated and reliant on partnerships.

- We also know that it is ethically right and operationally effective to work more in partnership with local and national organizations which are closer to affected people or organized by them.

Learning more about the theme of partnerships and volunteerism for humanity. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Singapore Red Cross

So, today, I want to talk share some ICRC thoughts on partnership and focus on four questions:

- What is partnership?

- How can we do it well?

- What does it look like in practice for ICRC?

- How ICRC can improve to do it better?

In doing so, I am drawing on two literature reviews on partnership which we carried out to help all of us at the ICRC understand the subject better. But before I look at these four questions, I want to stress that partnership is about relationships. It is about people doing things together with other people.

I also want to affirm that the art of partnership is not just a matter of collective partnerships in which organizations work together as various groups of people teaming up in inter-organizational partnerships.

Partnership is also inter-personal and intimate. It is about how two individuals work together in a humanitarian purpose at the most basic level of humanitarian action. At their best, we can talk of the millions of daily humanitarian interactions as personal partnerships of care.

The relationship between a medic and a patient is a partnership of two people working together in common cause: one concentrating on recovering and the other concentrating on treating and encouraging them in a partnership of healing.

The same is true of the member of a Restoring Family Links team working with a father to trace his lost daughter. They need to work together to bring about a humanitarian success. Even the blood donor is in a mysterious partnership with a person she or he will usually never meet. The flow of blood from one arm to another, carefully mediated by others along the way, is remarkable series of inter-personal links in a humanitarian partnership to save a life.

Volunteers make all the difference in partnerships of all kinds because they are fundamental to collective partnerships and intimate partnerships.

Volunteers are the building blocks of inter-organizational partnerships between our institutions, and they are also the human face of caring inter-personal partnerships between people working together one-to-one as humanitarian and victim.

1. What is partnership?

There are several different types of partnerships and we tend to enter different types for different reasons.

Different levels of partnership are usually described along a spectrum. At one end are minimal transactional partnerships in which relationship-building and common goals are not very important to the parties. At the other end, are highly transformative partnerships in which forming a new joint relationship to achieve deeply shared goals is deeply valued by the partners.

Volunteers make all the difference in partnerships of humanitarian action because they are fundamental to collective and intimate partnerships. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC

An (exaggerated) example of a very transactional partnership may be the commercial relationship between a trucking company and the humanitarian organization which contracts the company to move food in war or a disaster. The company has an essentially commercial goal and does not really mind whether they carry relief food to an IDP camp or a consignment of Cognac to a casino, just so long as their trucks are busy, and their profits are maintained.

In a transactional partnership, one party is typically in control and the other party is doing something largely for the purposes of the other. These minimal partnerships can be very successful at achieving certain objectives, but they are not build around shared purpose and shared values.

A transformative partnership is different. This may be two groups or two individuals who deliberately come together to combine what they do in a way that changes each one of them for the better and significantly transforms what they are able to achieve as a team - a new kind of effect which neither of them could ever have achieved on their own.

Importantly, an essential dimension of a transformative partnership is that it is genuinely a "two-way street" – each partner learns from each other, benefits from each other and is transformed by each other.

Every wise humanitarian will tell you this, humanitarian action is best done in #partnerships! @HSlimICRC at @SGRedCross #Humanitarian Conference pic.twitter.com/fNsTyg4xXo

— ICRC Malaysia (@ICRC_my) July 20, 2019

For example, two companies come together. One is a medical company that has found a new way to monitor blood pressure and the other is a digital company that specializes in developing apps and digital interfaces for business data which has a very wide take-up across the globe. Together, they find a way to make the health company's new blood pressure test available to millions of people with hyper-tension all around the world in a phone app.

This partnership transforms both companies. It diversifies the digital company from a finance data company into a major healthcare business able to realize its social values. It transforms the scale of the health company by giving it huge new remote reach to millions of stressed middle-aged business people prone to high blood pressure and vulnerable to heart disease and diabetes.

These transformative partnerships typically have common goals, shared values and, importantly, are based in the genuine collaboration of both partners and not the control of one party over the other.

People often illustrate the difference between minimal transactional partnerships and maximal transformative partnerships mathematically.

In a transactional partnership, 1+1=2, just as it always does.

But in a transformative partnership, something much greater than this is achieved so that 1+1=5.

A transformative partnership achieves a genuinely new thing for both parties which changes the game for them and for others around them. Transactional partnerships are relatively easy and low-maintenance if the unequal terms of control and the different purposes are understood and accepted by everyone. But they can feel conflicted, humiliating and abusive if one of the partners wants a transformative partnership.

We know this happens in the humanitarian sector when national and local organizations feel used and under-valued by domineering international partners, or where international agencies have felt used and abused by uncooperative or unaccountable local and national partners.

Transformational partnerships also require much more emotional and administrative work by all parties. But they can also deliver exponential and sustainable gains so their return on this extra investment can be high.

The ICRC head of policy, Dr Hugo Slim, gave a speech at the 5th Singapore Red Cross Humanitarian Conference on the theme of partnerships and volunteerism for humanity on 20 July 2019. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Singapore Red Cross

It is this type of deep transformative partnership that I will concentrate on today and they are generally much harder to do well.

2. How can we do partnership well?

The many studies of transformational partnership in practice in all areas of life have found several factors to be critical to success. Most of them mix ethical principles with working practices: doing the right moral things and doing practical things the right way.

At the outset, it is important to choose partners on the likelihood that your combined chemistry will deliver favourable conditions for effective teaming-up. There are perhaps three vital conditions to a good partnership.

First, as in the success of both arranged marriages and love matches, compatibility becomes a key ingredient to be sure of before you start.

This means detecting if you both have compatible goals and values, an ability to share power with one another and to give and take. Here, compatibility needs to be based on identical traits and a high level of convergence. You must share common values and goals. Divergent values and goals will not work.

It is then important to gauge if you have compatible work cultures and decision-making styles. Here, compatibility does not need to be found in identical traits and can be created by divergence. Partners may have diametrically different working cultures and styles which may be the very secret of their success.

Great exchanges & meetups with like minded partners & friends @SGRedCross #Humanitarian Conference today. #RedCross #RedCrescent #ForSocialGood #CareMore @HSlimICRC @ICRC_AsiaPac @IFRCAsiaPacific @SwissAmbSGP pic.twitter.com/o6ueNKVHE3

— ICRC Malaysia (@ICRC_my) July 20, 2019

One partner may be a cool-headed and plodding procedural decision-maker while the other is intuitive and impulsive. This divergence may produce a brilliant compatibility and fit if each partner can live with and appreciate the very different traits of the other, and if their working method is fundamentally constructive and mission-based.

The second key factor is mutuality which is essentially about ensuring there is a two-way street in the partnership with both partners able to share ideas and competencies to influence each other and develop a relationship which brings out the best in each other.

The magic ingredients here are equality, fairness, trust, transparency, communication and flexibility. If a partnership is to be genuinely transformative and sustainable it needs to be an equal one in which neither party dominates and disrespects the other. An unequal and disrespectful partnership may succeed in the short-term, but it will not last in the long-term because it creates too much pain and fury.

Fairness is not quite the same thing as equality. Partners may feel equal in their inter-personal working relationships and their respect for one another, but it is also important that inter-personal and inter-organizational equality is further manifested in the fair distribution of resources and results, whether these be operational gains, financial benefits or public recognition.

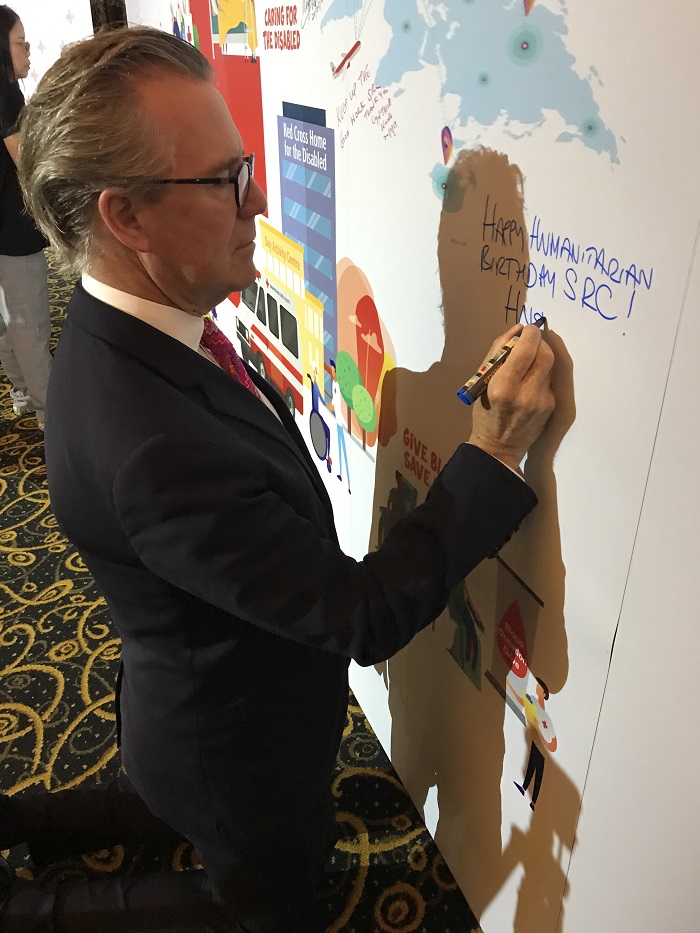

Dr Hugo Slim wishing a happy humanitarian birthday to our partner the Singapore Red Cross celebrating its 70th anniversary. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC

In humanitarian partnerships between national and international organizations, the challenge of asymmetric power – one party being much bigger, richer and better connected than another – can create deep structural problems of equality and fairness. These are hard to move through without a major transformation in the structure and resource sharing of the more powerful partner.

Such a commitment to change in which the bigger partner aims to give away power and resources in a major shift in power and business model is truly dramatic and needs to be balanced by significant organizational development support for the other partner as the scales of power and resources tip towards them. In our Movement, I am only aware of the Australian Red Cross truly trying to make this shift and transform its asymmetry of power and resources.

Trust and transparency also go hand-in-hand with equality and fairness. Each party must be able to trust the character and competence of the other, and so work trustingly and openly together. Finally, communication and flexibility are key mutual traits between both parties. Partners must be able to communicate well with one another, so they can understand one another on a long-term basis. Flexibility is also essential to tolerate one another's different cultures and styles, and to compromise and go with the flow of the other on occasions when agreement is hard.

The third key factor is the respective added-value of each partner to the other and to the overall goal and mission. Here, we are in the realm of complementarity – the added-value of what each partner brings to the partnership and how the partnership then moves to making something genuinely new and valuable happen.

This added-value must be weighed in qualitative and quantitative terms – the solid things a partner brings like resources, scale or depth, and the knowledge, skills and attitudes that partners bring. If compatibility, mutuality and added-value are the conditions of a good partnership, then the majority of partnership energy goes into making these work in the actual practice of partnership.

Here, everyone is clear:

Partnerships take real time and significant investments in relationships, common working practices, learning from failures and appreciating successes.

Inter-organizational partnerships require clear and written policies, rules and procedures that confirm shared objectives an enable an agreed working culture. Ideally, this would all eventually become second nature but in the early days the road is bumpy, and the partnership is truly tested in the very process of agreeing and setting these norms before it starts and then as it goes along.

3. What does Partnership look like in practice?

I now want to illustrate some of the different partnerships we have at the ICRC. I don't have time to make a detailed analysis of the particular type and quality of each example, but I hope they will give you a sense of what I have been talking about and some insight into our portfolio of partnerships at the ICRC, which is already extremely large and diverse.

- ICRC and National Authorities

One major and longstanding area of partnership is our legal and operational partnerships with national authorities. Our mandate to disseminate and develop international humanitarian law (IHL) means we have developed many partnerships with State armed forces with the common goal of educating and advising their forces and their wider societies on IHL. This role means we have set up many long-standing partnerships with State authorities around IHL objectives.

Next door in Malaysia, for example, we have seeded a joint regional IHL training and advisory centre with the National Defence University which will act as a hub for Asia. This aims to be a deep institution-building partnership that will combine the strengths of a Malaysian base, ICRC expertise and the active involvement of Asian States to create a regional service of IHL training, advisory and military policy development.

Humanitarians and representatives from governments, corporates, and foundations gather to discuss partnership and volunteerism in #humanitarian action. @SGRedCross @HSlimICRC #RedCross #RedCrescent #ForSocialGood #CareMore pic.twitter.com/nbnkvXzI4z

— ICRC Malaysia (@ICRC_my) July 20, 2019

At the global level, the ICRC has also taken on a convening role with multiple partner States to organize an annual high-level forum with a different rotating State partner every year hosting the event. The Senior Workshop on International Rules Governing Military Operations (SWIRMO) is becoming institutionalized amongst States as a significant space for them to share challenges and practice. Last year's forum was hosted by the United Arab Emirates and this year's forum will be hosted by Russia. This too promises to be transformative in the way in which a large number of States regularly share and discuss operationally focused IHL challenges and ICRC learns from this.

Our humanitarian action is also rich in operational partnerships with national and sub-national authorities. These partnerships are particularly true of our collaboration with authorities supplying and managing water, sewerage, energy and health. In many cities across the Middle East that are the sites of intense and protracted urban warfare, the ICRC has close and long-standing partnerships with water authorities, power supply authorities and health and agricultural ministries.

These partnerships focus hard on the mutual added-value and complementarity of the ICRC's humanitarian access, technical expertise, resources and staying power in conflict and the expertise, infrastructure and reach of national and local authorities. They involve agreements on shared commitments to service continuity, mixed teams, shared resources and clear multi-year plans.

These operational partnerships with national authorities involve activities as diverse as the repair and continuity of power stations, water treatment centres, clinics, hospitals, or the maintenance of cattle vaccination programmes and agricultural seed supply.

- ICRC and National Societies

The ICRC's "family partnerships" with other members of the Movement are deep, longstanding and complementary, even if they sometimes involve an asymmetry of power and resources in ICRC hands which do not meet conditions of equality and mutual added value and can be frustrating to National Societies.

Dr Hugo Slim with the Singapore Red Cross secretary-general Benjamin William. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC

In every country where the ICRC works, the National Society and its volunteers combine with the ICRC to add enormous value to the scale, depth and intimacy with which the Movement is able to work.

The national footprint of branches and their large numbers of volunteers typically extend the reach and scale of the ICRC by increasing our "operational surface" dramatically.

The face-to-face work of thousands of volunteers who lead much of the inter-personal contact in relief distributions, health services and restoring family links gives the Movement's work a personal intimacy and cultural affinity which the ICRC could never achieve alone.

It is here, in the real proximity of volunteers and victims together, if it is handled well, that the Movement achieves its profound inter-personal partnerships of humanitarian care.

Tony, a volunteer with @SGRedCross and also previously with Chinese #RedCross, sums up for us what volunteerism means to him. @HSlimICRC @ICRC_AsiaPac #RedCrescent pic.twitter.com/hZbSk7PU5n

— ICRC Malaysia (@ICRC_my) July 20, 2019

As we enter the era of climate crisis, the International Federation and its Climate Centre is becoming an increasingly important partner to the ICRC as we too engage with people's experience of the double effects of conflict and climate shocks on their lives.

The Federation's deep knowledge in the policy and practice of climate change response, disaster risk reduction and adaptation now need to become central to the way we work.

As we now also aim to become "climate smart" we too are benefiting from organizational development by the Federation. Our current partnership with the Climate Centre as we build policy, expertise and network on climate risk response is already proving mutually transformative: we need to learn climate risk skills, and the Climate Centre needs to better understand the combined effects of conflict and climate.

- ICRC and the families of missing people

We also form important partnerships at community level with community-based organizations (CBOs) formed by victim groups. Our work for missing people and their families is a good example.

Great exchanges and meetups with like-minded partners at the humanitarian conference. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Singapore Red Cross

In countries like Georgia, Nepal, Peru, Kosovo and Colombia, we have developed long partnerships with local and national family associations of the missing to address the fate of missing people and support their families. Our added value here is often in our neutral facilitation between local associations and public authorities and our forensics expertise. These partnerships are driven by a shared objective to realize the families' humanitarian "right to know" what happened to their missing relatives.

- ICRC and Kuwait

Our diplomatic partnerships are also deeply important to the ICRC.

The missing also led to an important diplomatic partnership with Kuwait, a country which has itself endured the sad suffering from missing people. This is one of many diplomatic partnerships we have with states that pursue common goals in humanitarian diplomacy.

In 2018, Kuwait and the ICRC both prioritized greater diplomatic action on the missing as a common goal and we then worked closely together with our policy, legal and diplomatic teams to support Kuwait's successful objective to secure the first ever UN Security Council resolution on people missing in armed conflict – UNSC resolution 2474 of June this year.

- ICRC and the World Bank

Our partnership with the World Bank is an example of a major institutional partnership intended to transform both the Bank and the ICRC. We have teamed up formally to improve each other's operational reach, expertise and policy and diplomacy on areas affected by conflict, violence and fragility.

Humanitarians and representatives from governments, corporates and foundations gathered to discuss partnerships and volunteerism in humanitarian action. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Singapore Red Cross

The actual administrative practice of this partnership is detailed and intense as we try to combine the ICRC's principle-based humanitarian action based heavily on trust with the World Bank's strong culture and processes of accountability and performance measurement. This is truly testing for both partners, but it means already that both parties are extending their reach: The Bank is investing in areas of Somalia and South Sudan which it could never usually reach, and the ICRC has been able to expand and secure operations here into the medium term. Both parties are learning new things.

- ICRC and ASEAN

We have also invested in developing a diplomatic and potentially advisory partnership with ASEAN here in South East Asia. This early stage process has involved us taking time to engage in ASEAN discussions and learning carefully from the ASEAN approach.

We in the ICRC have learnt two big things from ASEAN: the importance of a resilience approach to disasters in South-East Asia, and the priority of sovereignty, national leadership and local agency in the provision of humanitarian action.

This engagement has changed our humanitarian approach in South-East Asia and added value to the way we work all around the world. It has also led us and ASEAN to a careful appreciation of how the ICRC might add value across the region without interfering in the region.

These two areas are the dignified management of the dead, and mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) where both parties feel we have a complementary contribution to make to national efforts and regional response.

4. How ICRC can improve to do it better?

Finally, a few thoughts on how the ICRC can be a better partner. I think we need to focus on three things:

Dr Hugo Slim wishing a happy humanitarian birthday to our partner the Singapore Red Cross celebrating its 70th anniversary. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC

First, we need to prioritize and be strategic in our partnerships. Our new intention to work with others may lead to a rush of MoUs which lets 1000 flowers bloom and sets up rapidly organized partnerships with everyone.

Better perhaps would be for delegations and HQ teams to think hard about areas which would really benefit from transformational partnership and invest in making these work well. This should involve being opportunistic and taking risks but in areas we know to be important for the future.

Secondly, we need to be ready to change and to share power more than we cling to power. This is quite hard for the ICRC. In recent years, we have grown and expanded our own institution. Now we need to share. This means listening to others, creating level playing fields, living in a two-way street and transforming from an elephant into a fox.

Thirdly, we need to develop new partnering skills and metrics so that we are "fit for partnership". This means changing attitudes and processes so that we are better able to work with others and to appreciate the outcomes we generate together and not just the things we deliver on our own as the ICRC.