The devastating impact of sexual violence

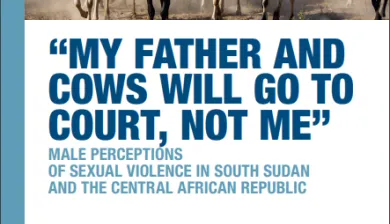

Despite being prohibited by national and international laws, sexual violence remains widespread and prevalent during armed conflict and other violence, as well as in places of detention and along migration routes. In conflict, it is often used as a tactical or strategic means of overwhelming and weakening the adversary by targeting the civilian population. Victims are disproportionately women, girls and sexual and gender minorities. However, men and boys can also be victims, and greater societal stigma and being held in detention put them at higher risk. Sexual violence constitutes a crime against humanity, a war crime, a form of torture and potentially an act of genocide. It can have serious consequences and is rarely an isolated issue.